Sometimes there are movies where the reasons behind the titles are clear. Croupier, for example, is about a croupier. No surprise there. Kill Bill is about killing some flute player called William who talks at the speed of snail. Amelie is about a girl called Amelie. You see them and can leave the cinema happy that whoever decides on the title made the right choice.

Sometimes there are movies where the reasons behind the titles are clear. Croupier, for example, is about a croupier. No surprise there. Kill Bill is about killing some flute player called William who talks at the speed of snail. Amelie is about a girl called Amelie. You see them and can leave the cinema happy that whoever decides on the title made the right choice.Then sometimes you leave a movie like The Hurt Locker and think to yourself, “What a great movie! Where is the bathroom? And where the hell did the title come from?” Not once is the phrase mentioned during the movie. John Hurt isn’t in it, nor a particularly significant locker. A consultation with the IMDB boards reveal that a hurt locker is somewhere you threaten to put people. As in, if your name is Inigo Montoya, and you’re standing in front of the person who killed your father, you’ll probably be putting them in a hurt locker. So there you go. Now you don’t have to wonder about it.

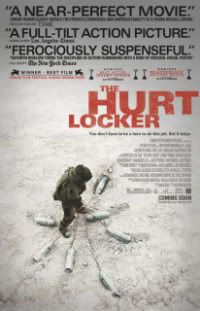

Not that you have much of a chance to. The Hurt Locker won seventy-eight Oscars for a reason. Whether it’s the best picture of the year is entirely subjective, but it’s better on the whole than Pocahontas-ripoff Avatar, though not better than the first fifteen minutes of Up. Still, it is an engrossing, tense and well-shot movie, and I have no qualms with it winning its seventy-eight Oscars.

As a rule, I hate war movies. Along with Westerns and Big Sappy Romances, I avoid them the best I can. Some suck me in, but generally I run far away from movies that involve blood, sweat, dust or tears. The Hurt Locker’s hype palled up with my excitement for the idea of a woman winning a Best Director Oscar for the first time, and there I was, stealing other people’s seats at the cinema so I could be closer to the screen and sucked in to this world.

Apparently it’s set in Iraq in 2004, though you’d never know the date (here I can’t help but mention the surfeit of anachronisms, like iPod touches and XBOX360s). William James has just joined the Bravo company’s bomb disposal squad after a brief cameo from previous team leader and excellent accent Guy Pearce as Matt Thompson. James is played by Jeremy Renner and is almost immediately shown as the kind of guy who thrives on risks and could be found in a B-grade movie yelling, “I don’t play by the rules, okay?” while their fellow team members scream, “You’re reckless!” He runs, not walks carefully, to bombs; throws smokescreen grenades without warning to his fellow team members; and takes off his bomb suit because it’s uncomfortable. His partners, by-the-book JT Sanborn and nest of fear Owen Eldridge, are less than pleased to have their lives treated so lightly, and so they should be.

But Bigelow’s strength lies in the fact that you don’t actually hate Renner. He’s there as a saviour, after all, and spends every assignment in what is essentially a suicide mission. He jokes and plays, does his job excellently, and is buddy-buddy with the local gangsta-talking ten-year-old DVD salesperson. He’s human, and for him, war is a drug. Disarming bombs is his fix.

The Hurt Locker, however, wasn’t quite as tense as I was led to believe. I wonder if it was because I went in imagining that in a movie about a bomb disposal unit, there was a chance that every character would die, and therefore didn’t invest myself in them as much as I usually do. I still cared for the characters, especially Eldridge, who was the most anxious about his job, his strengths, and his sanity, but I distanced myself from them.

Some unexpected star power in Ralph Fiennes, Evangeline Lilly and David Morse appear to remind us this isn’t a documentary, though the three team members have been around, but not entirely memorable for me until now. The movie is well-cast, beautifully shot, tense, gritty, and bloody. It manages to have less gore than you could expect for such a film bar one particularly upsetting scene regarding the disposal of a body bomb, and is probably the sweariest movie I’ve seen since the first three minutes of Four Weddings and a Funeral. It’s definitely a movie worth watching, as it does not glorify war as much as show how much it is deadly, terrifying, and able to alter the lives of soldiers irreparably.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Opinions, opinions! Come one, come all.