It has been a while since I’ve last posted here, but I promise I have a good excuse. On March 11—nearly a month ago now, lord—at some ridiculous time of the morning, I had a baby. Her name is Natalie Rocket and she is the cutest baby ever, and I’m not at all biased so you should take my word for that. Going to a cinema is a little tricky at the moment, but I’m hoping to head to some of those sessions you can take a baby to or head to the excellent Hoyts Victoria Gardens, whose cinema 2 has a crying room. I do, however, plan to let my kiddo be babysat for the first time when The Avengers comes out later this month, because I am in love with Captain America.

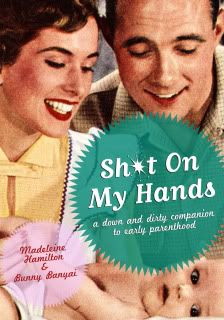

It has been a while since I’ve last posted here, but I promise I have a good excuse. On March 11—nearly a month ago now, lord—at some ridiculous time of the morning, I had a baby. Her name is Natalie Rocket and she is the cutest baby ever, and I’m not at all biased so you should take my word for that. Going to a cinema is a little tricky at the moment, but I’m hoping to head to some of those sessions you can take a baby to or head to the excellent Hoyts Victoria Gardens, whose cinema 2 has a crying room. I do, however, plan to let my kiddo be babysat for the first time when The Avengers comes out later this month, because I am in love with Captain America.I can review something, however: a lovely friend gifted me a copy of the small in stature but big in larfs book Shit on My Hands, by Madeleine Hamilton and Bunny Banyai. It’s pocket (or handbag or nappybag) sized and it’s about those first few terrifying days, months and years after you pop out a sprog. And it’s not at all twee, not even in a retro way (though it does have some hilarious retro pictures with terrible of-its-time kid-based advertising that must have decimated the population in the 1930s.) It’s just funny. And accurate. And there are swear words in it. Which you need to read when you’re trying not to curse so much in front of your new offspring.

Some choice phrases that made me laugh out loud include: “After you become a parent the nightly news may as well be called ‘terrible things that could happen to your child’.” (Incidentally I now cry at almost any ad with a baby in it because hormones.) On pink: “The birth of a baby girl...[is] also likely to herald the arrival of so much pink paraphernalia it’ll look like a flamingo has thrown up in your hospital room.” (True, but then as I only bought her blue or green clothes at least she now has an assortment of colours.) On competitiveness between parents about who has slept the least: “ ‘Well, my baby woke every fifteen minutes. And she vomited all over her sheets. Then she rang the Department of Human Services to tell them I was an incompetent turkey, before registering herself for membership of the Fascist Youth League.’ ” Look, there’s a million more things that are probably funnier, but unless I take notes (which I do at movies, and if I’m paying attention with books I fold over page corners when interesting stuff happens, but don’t tell my primary school librarian that or she’ll throw chalk at me) I am not good at remembering things. Especially now that I no longer sleep in any normal sense of the word. But take my word for it: this book is funny, and probably would be even if you don’t have kids or even want them, because then you can laugh at the pain of others. And if that’s not what life is about, I don’t know what is.

I give this book five out of five cute babies in hats, because I was in the mood for a laugh and I got one and anything more complicated than that can be saved for when I can walk properly again.

I give this book five out of five cute babies in hats, because I was in the mood for a laugh and I got one and anything more complicated than that can be saved for when I can walk properly again.