It’s not often a book can make me cry within four pages, but this one achieved it for me, on a crowded train no less. But I am a known crybaby when it comes to animals dying and people being sad about it, and as this book started with the death of the titular Alex—a thirty-one year old African Grey Parrot—and the emotional outpourings his death caused, I could hardly be blamed for getting all sniffly on the 1:42 to Flinders Street.

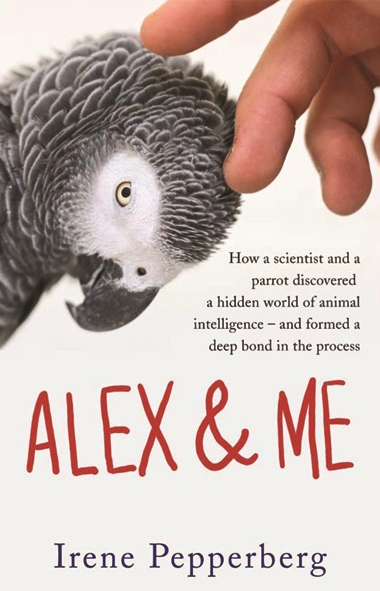

It’s not often a book can make me cry within four pages, but this one achieved it for me, on a crowded train no less. But I am a known crybaby when it comes to animals dying and people being sad about it, and as this book started with the death of the titular Alex—a thirty-one year old African Grey Parrot—and the emotional outpourings his death caused, I could hardly be blamed for getting all sniffly on the 1:42 to Flinders Street.Author Irene Pepperberg suffered through a painful upbringing, her cold mother ignoring her and her classmates taunting her. Solace was found in a series of companion animals in the form of birds, and that, paired with a love of science, meant that after a rocky beginning she found her calling: studying bird linguistics. It’s old news that parrots can talk, mostly in pirate speak or about crackers, but can their brains—the size of a walnut—comprehend more than repeating what swear words we teach them?

To summarise: yes. Alex learns fast, and develops amazing abilities. He can match colours to objects, for instance, calling a red block of wood a “four corner rose” (rose being easier for a parrot to say), but then develops further again. When shown piles of objects—a pile of one green object, two blue objects, etc—he could be asked, “what number green?” and answer “one” correctly. Well, like most test subjects, he answers correctly most of the time. What makes Alex so endearing is that he gets bored, yells “wanna go back!” if he’s done, or throws things on the ground, or answers incorrectly. Sometimes he even outsmarts his teachers: during one great scene, with the coloured objects in piles, Irene is asking him a question, and Alex keeps answering, “Five”. With only four piles—of one, two, three and four objects—Irene is confused why Alex is so completely wrong. Eventually, she says, “All right, smart alec—what colour five?” and Alex triumphantly answers, “None!” A parrot, with its teeny brain, has just come up with the concept of zero.

Irene is honest about the problems she faced. A broken marriage, long days, repeating experiments a hundred times to get the correct data, and, worst of all, the difficulties of funding her project. Universities toss her back and forth; she wins grants that can’t afford to give her the money she won; mostly, she relies on the friendly volunteers who help her with her training or donate to the Alex Foundation to keep it all going.

It’s a fascinating story, to be sure, but I found the actual writing a little...lacking. It feels, in a way, as if it’s written for older children; it’s pretty simply explained, there’s not much in the way of scandals or swears (I bookmarked a page where Irene is “pissed off”, but that was it) and it didn’t take me very long to read at all. Alex’s shenanigans with Irene, plane travel, his other teachers, and his newly introduced parrot buddies, are all a bit of fun but still smack of pausing for the delighted shrieks of children. The timeline confused the hell out of me, and made me wish I’d noted down where she was and when, because I didn’t always feel her portrayal was accurate. Irene would struggle to get funding for a single year, but then the next vignette would be from five years later, with Alex eating her proposal papers or similar tomfoolery. “How will I survive?” she will lament in 2000, then, in 2004, will jet around the world. This lack of explanation, along with not enough science behind Alex’s abilities, and not enough of Irene’s personal life, meant the book felt like an extended proposal; not fleshed out enough, just the bones of an interesting story. Irene’s own unwillingness to share what she thinks the conclusion of Alex’s results are, and her flippant remarks about how animals are still clearly second-tier, are written as if they are trying not to ruffle any feathers (see how I am hilarious with my puns) even if she truly believes that. It’s a frustrating, empty conclusion to a long experiment.

As someone opposed to the majority of animal testing, I at least enjoyed the fact that Alex and his parrot friends were well cared for, and not punished for being naughty or giving the incorrect answer. And as someone convinced that animals don’t deserve what we, as a planet, do to them, it is good to see an animal prove that those we eat for dinner are capable of more than we think they are. When Alex says his final words to Irene: “You be good. I love you,” you can’t help but be affected.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Opinions, opinions! Come one, come all.