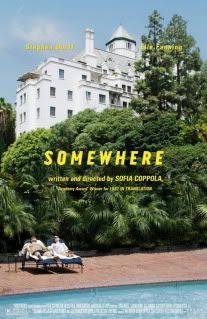

Somewhere out there, there are celebrities and CEOs and other famous, bored people who go see Sofia Coppola’s new movie and think to themselves, oh, OH, thank the lord someone has finally made a movie about how hard it is to be ridiculously wealthy. I’m not saying that being rich will buy you happiness—poor mental health transcends class, undoubtedly—but if you want me to watch a film about the sorrows of being able to fly anywhere, bonk anyone, and have everyone love you, then you better make it interesting. And Sofia, while you look like a nice person and I loved The Virgin Suicides and adored Lost in Translation (and as you are an ex-partner of Quentin Tarantino I will forever hold you in high esteem), I found Somewhere to be self-indulgent and dull. Sorry.

Somewhere out there, there are celebrities and CEOs and other famous, bored people who go see Sofia Coppola’s new movie and think to themselves, oh, OH, thank the lord someone has finally made a movie about how hard it is to be ridiculously wealthy. I’m not saying that being rich will buy you happiness—poor mental health transcends class, undoubtedly—but if you want me to watch a film about the sorrows of being able to fly anywhere, bonk anyone, and have everyone love you, then you better make it interesting. And Sofia, while you look like a nice person and I loved The Virgin Suicides and adored Lost in Translation (and as you are an ex-partner of Quentin Tarantino I will forever hold you in high esteem), I found Somewhere to be self-indulgent and dull. Sorry.

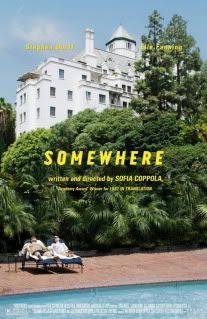

In LA’s Chateau Marmont, hotel to the famous and the place to do stupid things that end up on TMZ, famous actor Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff) is holed up waiting for the upcoming media junket for his new action flick and recuperating after a staircase-induced arm injury. He also drives a luxury sports car, as the five-minute opening sequence of him circling a racetrack in it will attest. In other news, his daughter Cleo (Elle Fanning) comes to stay for an indefinite period of time, dropped off by her mother. During this there is lots of brooding, no real talking for the first fifteen minutes, and no actual, long proper conversation for the entire length of the film, which is about an hour and a half, maybe less. So, the fact it’s short is a plus. Another point in the movie’s favour are the actors themselves—Stephen Dorff is quite likeable, Elle Fanning is great as Cleo, and the only other actor in it for any period of time, Jackass alumni Chris Pontius and his luxurious hair, is perfectly agreeable as Johnny’s best friend. Coppola herself turns up in a party scene, in case we hadn’t already thought that the life of a kid following her famous dad around hotels had any kind of autobiographical elements.

The movie is a series of vignettes about Marco’s existence over a few weeks, each scene carefully thought out and executed to perfection. We see him watch two awkward pole-dancing shows in his room (and in case you were worried it was too subtle, he falls asleep during the first one); look morose at his own party; sunbathe with his daughter; receive anonymous text messages calling him names; order room-service gelato with Cleo in an Italian hotel room; do a lot of driving; and have sex with everyone who makes eye contact with him. There is a startling dearth of speaking, and much like those scenes in Family Guy when Peter trips over and hisses over his hurt knee for five straight minutes, each moment is stretched out as long as is possible, then for, say, four minutes more. Thus poignancy turns tedious, and we physically feel the pain and torment of life as a star. It’ll make you want to donate to an ennui-based charity.

The juxtaposition of scenes seems important and telling, like when one of the pole-dancing scenes is followed by an uncomfortable viewing of eleven-year-old Cleo’s ice-skating routine. Hers is not a raunchy routine, nor is it perfect, and it gains the attention of Johnny like the dancers could not, but seeing her skimpy, glittery costume so soon after other skimpy, sexualised costumes is most definitely disconcerting. I don’t quite know what the message was. Dancing and metal props don’t mix?

Johnny and Cleo’s relationship doesn’t seem to be the point, as it follows a straight, drama-free trajectory. Johnny’s interactions with everyone are fairly mundane or friendly, his affairs only temporarily distracting. His hedonistic tendencies are on show, but still do not make him an unappealing character, meaning he lacks any real depth. When he calls one of his lovers to ask for company and she says no, he cries in despair, but with none of his past on display or many of his emotions or motivations revealed, I just couldn’t understand or care.

An enjoyable moment with a masseuse and affable characters, along with fine acting, lifts the movie out of the bin and possibly above the horror that was Tron: Legacy. The soundtrack has been much lauded but went largely unnoticed by me—which is not necessarily a bad thing, however, especially as I can’t stand Phoenix, who had a hand in it. It looks gritty and indie, and raw and true. But I still looked at my watch a lot, and wished Johnny would brush his hair just once, honestly.

In summary: Below Expectations. I feel she was striving for beauty and emotion, and instead got beauty and nothing else underneath, like when you’re walking through the Basement at Myer and think you see some well-dressed dude sitting down until you come to the devastating realisation that it’s a stragetically placed mannequin and will probably not appreciate your well-thought-out pickup line. And nothing will ever pull you out of a movie more than seeing the boom appear at the top of the screen not once, but twice. For shame. I’m shaking my head at my laptop now in pointed despair, Sofia.

If Tron: Legacy has taught me anything, it’s that we are now entirely spoiled when it comes to special effects. For all of Avatar’s faults, it showed just what CGI can do—and that’s pretty much everything, and with an extra dimension just to show off. So when you sit down to watch T:L, armed with your popcorn and the stupid happy smile you have on when you know you’re going to see a splashy neon actioner scored by Daft Punk, it is pretty much impossible to not be disappointed. Not by the action—the special effects in those were plenty amazing—but from the first moment Jeff Bridges rocks up, in a sappy prologue set a few years after the original Tron, you lay eyes on his youthfully digitised face and it’s all you can do to not storm off in disgust, throwing your popcorn at the projectionist and harrumphing right out of the cinema to lecture whoever was unfortunate enough to be working the candy bar at the same time.

If Tron: Legacy has taught me anything, it’s that we are now entirely spoiled when it comes to special effects. For all of Avatar’s faults, it showed just what CGI can do—and that’s pretty much everything, and with an extra dimension just to show off. So when you sit down to watch T:L, armed with your popcorn and the stupid happy smile you have on when you know you’re going to see a splashy neon actioner scored by Daft Punk, it is pretty much impossible to not be disappointed. Not by the action—the special effects in those were plenty amazing—but from the first moment Jeff Bridges rocks up, in a sappy prologue set a few years after the original Tron, you lay eyes on his youthfully digitised face and it’s all you can do to not storm off in disgust, throwing your popcorn at the projectionist and harrumphing right out of the cinema to lecture whoever was unfortunate enough to be working the candy bar at the same time.

Sam Flynn is a twentysomething brat, heir to his father’s huge tech corporation and a habitual prankster, driven to destroy the very company that pays for his bizarre car-garage home next to the river and forks out for his bail whenever he gets up to mischief. One day, a strange page (as in, those technological whatsits that no one uses now that there’s mobile phones) sends Sam to his father’s old arcade, where he stumbles upon ancient, eighties-era technology that does what it did to his father nearly thirty years ago and sucks him into a digital world. (Frankly, looking at dot matrix printers and clunky hardware and thinking that it created anything more elaborate than Tetris is a bit of a stretch, but that’s because I’m naive.) Captured almost immediately by the digital police squad, he is thrown unexpectedly into the fight of his life—and his father’s life, too.

Tron: Legacy has some stunning action scenes and despite my indifference to dance music in general, Daft Punk’s soundtrack is incredible and I am suffering some serious internal struggle over whether to download a couple of the songs or quit whining and just buy the whole album. The lightcycle fight, reminiscent of the original 8-bit Tron game, was great fun. Garrett Hedlund, as Sam, looks a little like Christian Bale but actually did a pretty good job despite being barely on my radar before right now. Olivia Wilde, as the older Flynn’s mysterious sidekick Quorra, has great makeup and sufficiently otherworldly eyes. And everything else about this movie is terrible.

Maybe I would have been able to overlook the slab of ham otherwise known as Michael Sheen’s ridiculously overdone club owner Zuse, the improbable fight victories, the heavily foreshadowed helmeted-foe twist and the forced, biblical plotline (Man creates world! Oh look, everything’s gone to shit. Better not do anything about it then, unless of course my son’s involved). Maybe I could have forgiven all of that if it wasn’t for one thing: Young Jeff Bridges. His digitally altered face is one of the worst things I have seen in cinematic history. As both the flashback Kevin Flynn, relating the story of the original Tron to his young son using figurines of himself and his cohorts, and as CLU, Kevin’s digital counterpart who—as doppelgangers always seem to do—has turned evil, he is a uninsured trip into the Uncanny Valley, his face devoid of texture and life, all the pixels of which seem to have been sent straight to his constantly moving hair. If he was in a video game, you’d consider him a great likeness, but this is a real movie, populated otherwise by real people, and as soon as he is next to them he looks completely fucking ridiculous. Maybe if they’d budgeted for an extra million dollars and made him spot-on realistic in the opening scene, you could buy the idea that he looks weird in the digital world for some digital reason, though no one else suffers from this ailment but him. The filmmakers could have made up some technological term to explain it away and I would have totally bought it. But I couldn’t. And basically, that poor effects work—especially when coupled with the rest of the film’s seamless CGI—ruined the entire movie, hands down.

The whole story is a bit ridiculous, and the action and plot so far-fetched, that sometimes I felt like Garrett Hedlund looked like he had fallen out of another, more serious movie, in which he played the straight man, and into this barrage of Bizzaro-Disney neon. He does his best, but is ultimately let down by poor scripting and awkward conversations with CLU, who appears to have suffered the ill-effects of a Botox jab. The movie probably would have been much better had they marketed it as a lengthy video clip for Daft Punk’s new album, and that way I would have completely excused any shoddy effects.

In summary: Below Expectations, in that I expect that a movie made in this day and age will look great, especially when that guy made Monsters in his bedroom and it looked a zillion times better.

In a world as familiar as the suburbs and as alien as a sci-fi movie, seventeen-year-old Ree Dolly is put in a terrible position. As the caretaker of her younger siblings now that her mother has lapsed into a speechless depression, she finds out that if her absent father does not turn up for his court date in a week, she will lose the family’s house and land—which he put up for bond. Trouble is, she doesn’t know where her crack-dealing pappy is, and the frightening inhabitants of her rural Missouri town take any requests for information as a personal threat. But with the wellbeing of her beloved family at stake, Ree is prepared to face whoever and whatever she needs to help them. While Ree’s younger brother and sister adore her and are good kids, they’re too young to look after themselves, and Ree has very few people to turn to. Teardrop—her missing father’s brother—is a scary, violent man, haggard and brutal, and aware of the code of honour within the society they live in. Her friend Gail is stuck at home with a baby and her unwilling, angry-looking spouse, unable to offer Ree the help she needs in her search. As a determined Ree asks questions of everyone within her realm of knowledge, the bleak landscape and the community do their best to stop her.

In a world as familiar as the suburbs and as alien as a sci-fi movie, seventeen-year-old Ree Dolly is put in a terrible position. As the caretaker of her younger siblings now that her mother has lapsed into a speechless depression, she finds out that if her absent father does not turn up for his court date in a week, she will lose the family’s house and land—which he put up for bond. Trouble is, she doesn’t know where her crack-dealing pappy is, and the frightening inhabitants of her rural Missouri town take any requests for information as a personal threat. But with the wellbeing of her beloved family at stake, Ree is prepared to face whoever and whatever she needs to help them. While Ree’s younger brother and sister adore her and are good kids, they’re too young to look after themselves, and Ree has very few people to turn to. Teardrop—her missing father’s brother—is a scary, violent man, haggard and brutal, and aware of the code of honour within the society they live in. Her friend Gail is stuck at home with a baby and her unwilling, angry-looking spouse, unable to offer Ree the help she needs in her search. As a determined Ree asks questions of everyone within her realm of knowledge, the bleak landscape and the community do their best to stop her.

Chris pondered aloud if the camera could have caught a flash of green grass or clear skies if only it had moved a bit either way; as it was, Winter’s Bone’s cinematography catches a place that is universally grim. Everything is cold, and worn, and old, and the world I am familiar with—happiness, smiles, friendliness—seems so impossible to get to that it is hard to believe cushy American movies are filmed on the same continent (and that my dear friend Lilli was in the same state recently having a total blast.) The gardens and houses show a world where perhaps in the past life was brighter: toys may have been new, machinery free of rust, houses freshly built. Drugs have choked the town, with its inhabitants mostly made up of crystal meth dealers and users, leaving everyone drawn and with the alarming look of someone high, or waiting for the next high. So chilling are the cast that Teardrop, constantly snorting from his little baggie, terrified me until I IMDb’d him in the car on the way home and realised he was actually John Hawkes, recently the cause of my adoration as the will-they-won’t-they father in Miranda July’s excellent Me and You and Everyone We Know. It was such a brilliant turn and I was so completely fooled that it reminded me just how plain talented actors can be. Jennifer Lawrence, as the savvy Ree, is also amazing, stopping at nothing—no matter what the threat—to save her family.

The movie manages to put a few interesting twists into the characters, turning two cinematically-hated tropes, including an army recruiter, into basically the kindest people in the film. As Ree hopes to join the army, asking when the promised $40,000 would arrive, the recruitment officer tells her gently that it wouldn’t be for a few months, and that she really needs to rethink joining the army if money is her sole motivation, and that caring for her family is a much more important job. Their heartfelt discussion is, frankly, shattering, as it was the only time I had thought: join the army! Get some money! This really is your only choice! Instead of: run away! Army bad!

Winter’s Bone is probably going to take over the Oscars, and it should. It really is a marvellous film: knock-you-down devastating, depressing and pearl-clutching, with a lake scene so viscerally horrible near the end that will have you wanting to hug Jennifer Lawrence should you ever see her in the street shopping for groceries. There is, in Ree and her siblings and the home of her father’s lover, little sparks of hope that make the movie beautiful through its cheerless exterior. In this, it shares similarities with John Hillcoat’s The Road, though Winter’s Bone conveyed a world that Hillcoat (well, Cormac McCarthy) needed an apocalypse to create. Why so dramatic, when there is such horror in the world we already have?

In summary: Above Expectations. This is a tremendous film, never tedious, and with characters you feel are desperately real and whose determination you cheer (or whose downfall you secretly wish for.) The only fault, for me, was the addition of a tree-felling dream sequence. I don’t believe a good dream sequence has even been filmed (or written.) Feel free to shoot me if you wish. (And hush, Alice in Wonderland is not counted.)

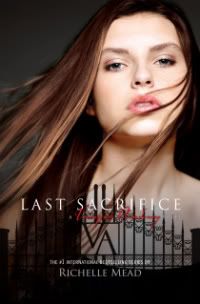

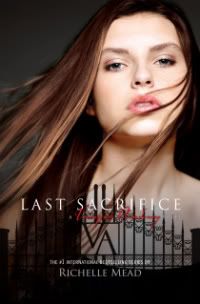

As someone who rarely reads books that are part of an ongoing series—apart from Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid and Stephenie Meyer’s satirical Twilight series, I can’t think of anything since Harry Potter—making it to the sixth book in a row is a real effort and means that something must be right. While this is true—the Vampire Academy series is great fun—there is also a lot wrong with this book.

As someone who rarely reads books that are part of an ongoing series—apart from Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid and Stephenie Meyer’s satirical Twilight series, I can’t think of anything since Harry Potter—making it to the sixth book in a row is a real effort and means that something must be right. While this is true—the Vampire Academy series is great fun—there is also a lot wrong with this book.

To rain down spoilers from the first five books in the series, Last Sacrifice opens with our heroine, Rose Hathaway, locked away in jail accused of the murder of Tatiana, queen of the Moroi. Rose and Tatiana didn’t particularly get along—Tatiana had recently passed a law lowering the age that guardians graduate and become fighters. As Rose is a guardian herself, trained to protect the Moroi—the good, consensual-bitey vampires—from Strigoi—the bad, murdery kind of vampire—she is not well pleased with the decision, but not enough to kill Tatiana. After a previous court outburst and some shifty bribing, Rose has been framed for the crime—but by who? As she is stuck in her cell, her friends and family do all they can to help her, from trying to find the real perpetrator to using a dramatic diversion to bust Rose out of the big house.

The Vampire Academy novels rely highly on throwing twists and shocks in every chapter, so I’ll try not to say much more. Suffice it to say the series relies heavily on action and drama, neither of which really can happen in a jail cell, so Rose is out and about breaking hearts and staking vicariously shortly into the book, making new friends and new enemies and smooching—well, who? Longtime readers will be either Team Dimitri (Rose’s first boyfriend, guardian trainer and someone who was turned Strigoi then brought back by Rose’s best friend, Lissa) or Team Adrian (when Dimitri became evil then broke up with Rose, in that order, Adrian was there to pick up the pieces and smoke heavily in the background.)

As Rose blusters her way around the countryside, her best friend Lissa, who brought Rose back to life during a car accident years before, is coping with her own dramas back at court, where she is thrown into much bigger turmoil than expected. The series is written through Rose’s dramatic, biased point of view, but due to her resurrection she shares a bond with Lissa that means she can see from the other girl’s point of view. Doing this means Rose is free to keep tabs on what’s happening in court even while getting up to more hasty crimes in the American backwoods.

It remains good, action-packed fun, sufficiently dramatic, a bit sexy (but not too much for the innocent eyes of teen readers—most dalliances get interrupted at inopportune times) and full of the characters you’ve enjoyed meeting in the past. Rose is flawed, has a quick temper, but is pretty funny and does what she thinks is best, which means she is mostly likeable.

But lord, sometimes you want to just stake her in the heart. Sometimes she is so stupid, or brash, or insensitive, that you really wonder if it would be so bad if she got executed for treason after all. Rose is a pain in the ass, and if it wasn’t for the fact that she is tall, fit, gorgeous, and could beat up anyone who looked at you funny, would she ever get as many marriage proposals and men willing to do anything for her? Her decisions are frequently annoying, and her reasoning behind the eventual relationship choice she makes feels very pasted on and does not compute with how the gentleman in question has appeared in the past.

The book could have done with a good dose of editing and the removal of one chapter ending early in the book that put my teeth on edge far too soon. The bond between Lissa and Rose has been a large part of the whole series, so when chapter two ends with Rose waking up, panicked, and the last lines being:

“What I found was...nothing.

The bond was gone.”

it’s serious business, you know? So when chapter three starts like this:

“Well, not gone exactly.

Muted.”

you feel like you’ve been cheated out of your emotions. I actually ended up marking a lot of pages in the book with scraps of paper if I came across questionable writing or plotting, but half of them fell out when I was flicking through just now to get to chapter two, so you might have to take my word on that. (One seemingly petty marked page found that someone knocked on Rose’s door in a “discrete” manner.) While I’m sure author Richelle Mead has had the series planned out in her head for some time, the eventual unveiling of who really killed Tatiana is actually kind of mean and annoying rather than a lightbulb moment where you think “of course!”. Some characters seem like red herrings, or just introduced to fawn over Rose, and some questions are still left unanswered. While the series will be continuing on with another Vampire Academy series forthcoming, one that won’t follow Rose—but apparently she will be around, so it won’t quite be the last we see of her—perhaps some of the loose ends will be tied up, but I don’t think I can be bothered reading any further now that this story has essentially reached its end point. I’ll just harass some poor teenage girl into reading them and telling me what happens to Rose in the future. “Does she get married? Does she have cute babies? Does she ever get the cute but inappropriate clothes she often finds herself wearing caught in any machinery and killed? TELL ME!!”

In summary: Below Expectations. I had hyped myself up into thinking the series was much more well-written than it is. It was still enjoyable enough, and with so many surprise moments it’s a page-turner, but I won’t read anything else by Mead because I am sick of all these improbably attractive people and their fantastical castle-related lifestyles. I really just don’t care any more.

It took filmmaker Samuel Moab almost thirty years to tell his story. It has been that long since the first day of the Lebanon war—June 6, 1982—when he was just twenty years old, and I was a few days off being born. As I was rolling around in the comfort of my mother’s womb, Moab sweated and shook behind the trigger of a tank cannon, tasked with the job of shooting anything that moved. It’s a thankless job: don’t shoot, and you may put all your comrades in danger; shoot, and you might kill an innocent civilian. Moab attempted to make this film years before, but couldn’t, the horrors of his experience too raw to recount. Finally, he was able to finish the script and make the movie he needed to. On a tight budget, and shot entirely within the confines of a tank—bar the brief opening and closing scenes—what he produced has won him accolades worldwide.

It took filmmaker Samuel Moab almost thirty years to tell his story. It has been that long since the first day of the Lebanon war—June 6, 1982—when he was just twenty years old, and I was a few days off being born. As I was rolling around in the comfort of my mother’s womb, Moab sweated and shook behind the trigger of a tank cannon, tasked with the job of shooting anything that moved. It’s a thankless job: don’t shoot, and you may put all your comrades in danger; shoot, and you might kill an innocent civilian. Moab attempted to make this film years before, but couldn’t, the horrors of his experience too raw to recount. Finally, he was able to finish the script and make the movie he needed to. On a tight budget, and shot entirely within the confines of a tank—bar the brief opening and closing scenes—what he produced has won him accolades worldwide.

I will do everything in my power to not see war movies, generally. It seems awful and shallow to avoid what is a grim reality for a huge part of both history and present, but I usually find the machismo and bloodshed just too sickening. You’re much more likely to find me at a 3D kids’ flick laughing at a fart joke than in an arthouse cinema stroking my beard about the poignancy of camera angles. Still, when a movie receives as much attention as Lebanon it seems a good reason to get over my dislike and watch something so worthwhile.

Shmulik is a gunner, dropped into the belly of an Israeli Defence Force tank with loader Hertzel, driver Yigul, and officer Assi. They meet and shake hands, then are mobilised immediately to get to a road and wait for further instructions. When a car approaches, they are given their task: shoot to their left, then to their right, and if they don’t move, shoot out their engine. As someone who has previously “only ever shot barrels”, Shmulik freezes, endangering everyone around him; from that moment, the stage is set as real people—not Rambo-type heroes with oversized muscles and bandannas—are shown fighting with their emotions and each other as they struggle to survive the first day of the Lebanon War. Outside, the unit’s commander and his soldiers are face-to-face with the horror, with hostage-takers and the dead or injured, and trying with the tank to clear a freshly razed town. As the situation worsens, those in charge must deal with changes of plan, lack of backup and the subversiveness of inexperienced and frightened soldiers.

After seeing Buried and Devil I worried that 2010 was overdoing the claustrophobia* movie, but this felt much different. It is still an oppressive atmosphere, crowded into a tank with four men whose only view to the outside world is through crosshairs, but at least there are other people to see. With the faces of those destroyed by the war in sharp relief, however, it is not a beautiful world, but a devastating one. As one man stares down the sight, sharing a table in a town with a friend lying dead and bloody opposite, the trauma of the experience for everyone involved is made clear.

Immersive from the moment Shmulik lowers himself into the tank, Lebanon is a gripping and awful movie, with only one real moment of levity during a tale of an ill-placed hard-on in front of a teacher tasked to accompany a teenage Shmulik home after the death of his father. It’s hard to crack a smile during the story anyway, told as it is to improve the mood of the men in the tank, feeling alone and desperate in their dirty, aged, shelled tank with the walls covered in post-attack oil and soup croutons.

The sound design is ominous and alarming, the cinematography amazing when you consider the limited space. It is not a comfortable movie, soaked in blood and tension, but with tender moments as soldiers try to reach out with humanity during even the worst times in war. The devastation and tension of the first ten minutes does have the detrimental effect of causing the rest of the movie to feel slower and (mildly) less traumatising.

In summary: Meets Expectations, which were high after the glowing reviews. Lebanon is an important and devastating movie, and I am full of admiration for Samuel Moab in making such a personal film.

*Chris told me I wasn’t allowed to use the c-word word in my review because “everyone else has”, but that’s like not saying the word “tank” in this movie. If you suffer from claustrophobia, you probably shouldn’t see it, unless you’re at the Open Air Cinema and you’re driving home afterwards in a convertible.

Somewhere out there, there are celebrities and CEOs and other famous, bored people who go see Sofia Coppola’s new movie and think to themselves, oh, OH, thank the lord someone has finally made a movie about how hard it is to be ridiculously wealthy. I’m not saying that being rich will buy you happiness—poor mental health transcends class, undoubtedly—but if you want me to watch a film about the sorrows of being able to fly anywhere, bonk anyone, and have everyone love you, then you better make it interesting. And Sofia, while you look like a nice person and I loved The Virgin Suicides and adored Lost in Translation (and as you are an ex-partner of Quentin Tarantino I will forever hold you in high esteem), I found Somewhere to be self-indulgent and dull. Sorry.

Somewhere out there, there are celebrities and CEOs and other famous, bored people who go see Sofia Coppola’s new movie and think to themselves, oh, OH, thank the lord someone has finally made a movie about how hard it is to be ridiculously wealthy. I’m not saying that being rich will buy you happiness—poor mental health transcends class, undoubtedly—but if you want me to watch a film about the sorrows of being able to fly anywhere, bonk anyone, and have everyone love you, then you better make it interesting. And Sofia, while you look like a nice person and I loved The Virgin Suicides and adored Lost in Translation (and as you are an ex-partner of Quentin Tarantino I will forever hold you in high esteem), I found Somewhere to be self-indulgent and dull. Sorry.