In early 2008 I was handed a copy of the book The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by a sales rep at work and told it was going to be the next big thing. I have heard this spouted before—about thirty-seven times a week for ten or so years—but this was the one time it was absolutely and utterly true. And unlike Harry Potter, I was there at the start, telling people about this new book and selling it without the power of 21 million books sold and three movies behind it like it has now. Sure, it’s a pathetic claim to fame, but in the bookselling world, you take what you get. (I had a ghastly-covered advance copy of Twilight once too, but alas had to give it back to the rep once I’d finished reading it. Now they’re selling on eBay for nearly two thousand dollars and I wish I had pretended to lose it.)

In early 2008 I was handed a copy of the book The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by a sales rep at work and told it was going to be the next big thing. I have heard this spouted before—about thirty-seven times a week for ten or so years—but this was the one time it was absolutely and utterly true. And unlike Harry Potter, I was there at the start, telling people about this new book and selling it without the power of 21 million books sold and three movies behind it like it has now. Sure, it’s a pathetic claim to fame, but in the bookselling world, you take what you get. (I had a ghastly-covered advance copy of Twilight once too, but alas had to give it back to the rep once I’d finished reading it. Now they’re selling on eBay for nearly two thousand dollars and I wish I had pretended to lose it.)

Stieg Larsson would have been a tremendously rich man had he been alive to reap the benefits of the Girl empire. Alas, he died before publication of his trilogy, and caused not only the adoration of an entire planet, but a scandalous controversy involving his defacto widow unable to get any of the profits because under Swedish law their length union counts for nothing. I should point out here that this has no bearing on the movie or the books; I’m just a gossip. Like an overprotective member of Stieg’s legacy, I was hesitant of the movie to begin with, angry at Noomi Rapace’s version of Lisbeth Salander being too pretty and Michael Nyqvist’s Mikael Blomkvist being not pretty enough. I was sure it would all go horribly wrong and that the only person to do it justice would be director Quentin Tarantino, who at one point was rumoured to have his paws on the American version. But after seeing this, I rescind that statement and go back to my initial stance that the original movies are always better than remakes and America should just keep their greasy mitts off.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo—or Män som hatar kvinnor, translated as Men who Hate Women—is an excellent thriller. Of course it’s hard for me to be entirely impartial as I know the story of the book’s characters so well after three books and eight million billion pages (which is what it looks like when you see them next to each other) and feel quite attached to them. But I was anticipating a crap B-grade movie and did not get one. While we saw it on a Sunday afternoon in a fairly posh suburb, I was still surprised to see we were the youngest audience members by a good twenty years. Having read the books and flushed red from the violence of some of the scenes, I was mildly worried that half of the crowd might be unconscious from copious fainting in their seats when the lights went on. They all bore it remarkably well, even the woman in the back row WHO APPARENTLY NEVER LEARNED THE RIGHT NOISE LEVEL FOR WHISPERING. And there are some truly horrific scenes.

Stripped down to the bare bones of the story and neglecting some key characters, the film is the story of investigative journalist Mikael Blomkvist, convicted of libel against corporate bastard Wennerstrom, and given the opportunity to lie low for a while by a desperate Henrik Vanger. Vanger’s niece Harriet went missing forty years ago and he is attempting one last time to find out what happened, employing Blomkvist—a determined and thorough journalist—to investigate. Investigating Blomkvist himself is young computer hacker Lisbeth Salander, a young woman shown no benevolence by authority figures and who reacts to life accordingly. She is a fabulous heroine, merciless and unforgiving, but only towards those who deserve it. Her scenes are by far the most upsetting in the movie, as she is abused by the man appointed as her guardian by the state—and then strikes back. I had to put my popcorn down and hold onto Chris’s hand for those parts.

And with that, I was completely sold. Rapace wasn’t too pretty at all—she is attractive, but plays Salander as gritty and boyish as she is in the book. Nyqvist endears with his adorable smile and plays Blomkvist’s earnest honesty and quests for truth well. Peter Andersson as Salander’s guardian Bjurman plays for chills and succeeds; Sven-Bertil Taube is pitch-perfect as hangdog capitalist Henrik Vanger. A lot was missed or glossed over in the making of a film, but that happens in any adaption, especially one where the source book runs at over six hundred pages. While the dense plot of the book was enthralling as I love it when everyone gets a backstory so their motivations are clear, the movie was whittled down to what made for interesting viewing and story clarity. I hope, however, this won’t affect the next two movies.

I imagine the actress who played Blomkvist’s editor Erika Berger was thrilled when she got the part, only to find she appeared in two scenes and spent most of them looking like a sad puppy in the direction of Blomkvist. In the books she is a huge part of the story, knockout gorgeous, feisty and tough, parading around looking attractive and keeping Blomkvist’s outside world afloat. Along with Salander’s original guardian, the lovable but physically incapable Holmer Palmgren who gets absolutely no screentime in the film, she caused me to feel a sad loss. I also missed the nudity that I was expecting in a Nordic tale of a man who tenderly bonks just about every girl who says hello to him; in the movie, Blomkvist is much more restrained and “gentlemanly” according to social norms. The books delight in uncommon relationship dynamics; Erika is a polygamist and no one minds, Salander loves men and women equally in her bed, as long as they are there on her terms.

The setting, winter in Sweden, is absolutely beautiful; all picturesque mansions covered in snow and roads that defy gravity. While the actors and script shine, I’d be lying if I said it was flawless. The music felt heavy-handed at times, making some scenes slightly laughable. If a breakthrough was made by Blomkvist or Salander, it was accompanied by superimposed photographs and a pointed explanation. Movies that don’t give their audience any credit can be very frustrating, but I forgive this one. Not holding back on the attack on Salander—an important part of the book, if not almost unbearable—gets those points back.

One more thing: I was notified halfway through the film by the attractive young gentleman beside me that I was misinterpreting Salander’s reactions. Chris once studied linguistics and learned that what we consider a short, shocked intake of breath was just the everyday pronunciation of “yes” and “no”. So don’t think Salander’s shocked by what she’s discovering, despite the fact that you might be.

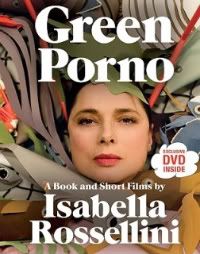

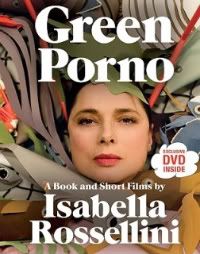

Now, boys and girls, we are going to learn about reproduction. No, no, religious fundamentalist parents in the back, sit down and be calm. This isn’t a lesson about condoms and abstinence. This will be a lesson about how marine animals get it on, and here is your instructor, model and actor, Isabella Rossellini. (pause for applause)

Now, boys and girls, we are going to learn about reproduction. No, no, religious fundamentalist parents in the back, sit down and be calm. This isn’t a lesson about condoms and abstinence. This will be a lesson about how marine animals get it on, and here is your instructor, model and actor, Isabella Rossellini. (pause for applause)

This is what my lesson notes would look like if I was an educator and I was teaching biology. Luckily for everyone, I am not. It’s unlucky for some, however, because Green Porno’s educational experience in marine mating rituals—told with paper sculpture and puppets and starring as part of the mating couple/threesome/spawning festival is Isabella herself, all dressed up and waiting for a good time. Or a bad one, if you’re a limpet: the girl limpet is on a rock, many other limpets come and attach themselves to her, and become male; they all have a frenzy of mating and then the girl dies. But it’s okay, because the limpet closest to the dead girl will become a girl, and it all begins again; a big fiasco of bonking and carnage, kind of like a teen horror movie. Such are the things I have now learned from Green Porno.

Green Porno started as a series of short environmental films destined for the internet; Rossellini did not realise that they would be as popular as they are. (A beautiful star doing a series of sex-saturated movies? Who would be interested in such a thing? Only everyone, silly Isabella.) One experimental series became two, then three; the first two are included on a DVD that comes with the recently-released book. (Series three is on the marine life that the book explores.) This book manages to be shocking, because it uses scandalous words like “anus” and “vagina” and has a Rossellini dressed up as a boy whale with a six-foot penis having sex with a girl whale made out of cardboard; still, it is family-friendly in that it only conveys (albeit in a papery way) what actually happens when animals mate, as, you know, they generally do no matter how horrified prudish people are about it.

The sculptures are actually quite lovely. Everything bar Isabella herself is made of paper or foam rubber; even the kitchen she stands in while contemplating a tasty plate of prawns (before learning about bycatch and consequently losing her appetite) has paper cupboards and drawers and cooktops. One of the most beautiful stories is the sad tale of the squid, who is having a passionate ten-armed hug—“but not all of them are arms, if you know what I mean”—and then rises to the surface only to be caught by a big paper fishing trawler. The squid, with Isabella inside, lights up with different colours depending on its mood: red for angry, and a glorious white when it’s in love (that is my own romanticised opinion of horny, don’t listen to me); the night sea is a gorgeous deep blue and even the boat, enemy as it is, is strung with fairy lights and brings a lovely ethereal feel to the book. The effort that must have gone into these is astounding, because they look incredible, though still retain a humorous DIY-feeling, like the boy anglerfish portrayed by Isabella with an enormous rubber nose and a kind tooth on the top of her head, which is used to penetrate the girl fish’s belly so the boy fish can fuse itself to her (and what a shame our own mating rituals aren’t like this, am I right?)

The final chapter is on genitals, starring many cardboard creations of the many terrifying-looking marine penises that are out there. It ends on a discussion that touches on the issue of consent, even though in the marine world it seems to be more about getting fought for than picking a guy out of a crowd, and then finishes with talking about how women have their own tunnel, “and it would be a labyrinth. It’s intricate and it’s unique. And it’s species specific...so that I am not screwed by a bear.” Hmm, perhaps not so family friendly there, unless you want to give your small chidren terrible nightmares.

Frankly, this strange book is absolutely entertaining, and with her side notes and facts on overfishing and other marine dangers, it doesn’t hide that there’s an important message too, and one that Isabella—now a vegetarian—took seriously. The accompanying DVD will have you snickering away to yourself as Rossellini plays the different animals, though it’s also something you perhaps don’t want to show during a family birthday. As an earthworm, defecating and peeing and then fornicating, saying slyly: “To have babies, I will have to mate with another hermaphrodite...in the sixty-nine position.” As a snail: “I can produce darts. I use them to inflict pain on my partners before mating. It turns me on.” The Sundance Channel’s Youtube has a few of these shorts for you to watch and be unable to resist commenting “OMG LOL” on. This book is not cheap, yet worth every penny, especially when you whip it out at your next dinner party to show off to your friends how cool you are. Because you will be with this in your collection.

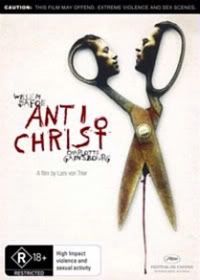

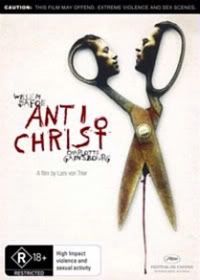

Lars Von Trier’s newest film has now proudly usurped the top spot previously held by In the Realm of the Senses as Worst Date Movie Ever. What these two movies share are unsanitary, health department-unapproved scenes of genital mutilation, but Antichrist wins because the title is easier to say, and it lacks the, er, romance of the other. Much has been made of the scene in Antichrist, but if you are one of the few people who haven’t heard about it, I won’t go into details. For one, it’s icky. For two, knowing what was coming dulled the shock. Which is not to say that I wasn’t shocked by Antichrist; hell, it is impossible not to be. No one appeared to be on neutral ground in regards to it: reviews all gave it five stars or one. I can’t quite understand giving such a beautifully shot, undeniably eerie film one single star. But it takes all kinds, etc, and some of them will obviously be people who are wrong. (I am always right, in case you were wondering.)

Lars Von Trier’s newest film has now proudly usurped the top spot previously held by In the Realm of the Senses as Worst Date Movie Ever. What these two movies share are unsanitary, health department-unapproved scenes of genital mutilation, but Antichrist wins because the title is easier to say, and it lacks the, er, romance of the other. Much has been made of the scene in Antichrist, but if you are one of the few people who haven’t heard about it, I won’t go into details. For one, it’s icky. For two, knowing what was coming dulled the shock. Which is not to say that I wasn’t shocked by Antichrist; hell, it is impossible not to be. No one appeared to be on neutral ground in regards to it: reviews all gave it five stars or one. I can’t quite understand giving such a beautifully shot, undeniably eerie film one single star. But it takes all kinds, etc, and some of them will obviously be people who are wrong. (I am always right, in case you were wondering.)

Antichrist’s prologue is a soft, exquisitely shot portrayal of a young child climbing to his death while his parents make sweet, X-rated love in the other room. What follows is his parents, never named but played unflinchingly by Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg, trying to deal with their grief and guilt over what happened. He is a psychologist, and she is depressed: the solution, he feels, is to take her to their summer cabin to confront her emotions, and to treat her himself. It turns out that letting two emotionally fraught people stay in an isolated cabin, surrounded by only the cruelty of nature, was not his greatest idea. Well, he was not so long ago a goblinesque supervillain, and thus is clearly not a man of fantastic foresight.

I had planned to do other things as we watched this film, now available on DVD. I didn’t anticipate enjoying it, and besides, I had important pointless things to look up on the internet. About two minutes in, I put the laptop on the floor, and didn’t pick it up again until the movie was over. What seems like a small plot expands into something much more devastating and serious, as he and she explore their reactions and feelings and have a whole stack of gritty sex. Neither are beautified for the film, but they don’t need to be: Dafoe’s face could carry a film on its own, and Gainsbourg is appealing even when naked, raw, covered in twigs and masturbating relentlessly in the roots of a tree. A movie with such unbridled sexuality and nudity is a brave choice and one I am always in favour of, because I am sick of the only nudity in movies being when a socially-beautiful woman takes off her top for some waist-up-only sex scenes. Male nudity is a rarity and if you ever wanted to see Dafoe in the buff, you now have your chance; much of it may be stand-ins, but some scenes are not.

He and she fight and make up, make breakthroughs and regress. Each are flawed: he treats her as a patient and not a person, an experiment but not his wife, until she advances on him; she is hiding secrets about her last summer in the cabin, alone with their son. She uses sex as a distraction, but he acquiesces. They are the only two people who speak in this movie, and apart from their doomed son, other characters are only in it for less than a minute. Nature—both kinds—shows its beauty and its unsentimental reality through haunting dream sequences and scenes struck through with animal terror.

There will be parts of this movie where you cover your eyes and peep through your fingers. There are visceral reactions to be had from this film, but you won’t be able to look away. As striking as it is horrifying, it is an incredible movie and while I don’t give stars, I am completely astounded to find anyone giving it only one. (Yes, Leigh Paatsch, I’m looking at you.)

Seriously, however, don’t take my initial statements lightly. It is not a date movie. There is one scene in particular that will destroy any kind of smooching mood for at least twenty-four hours. Hire Star Trek, and don some Spock ears for some evening romance instead.

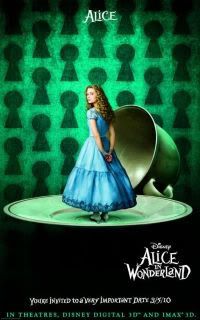

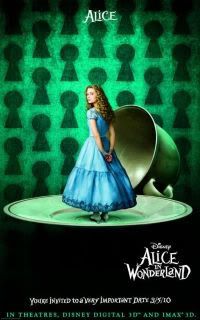

At some point in this Tim Burton movie you may notice that the characters are calling their three-dimensional world “Underland” instead of the “Wonderland” you’re accustomed to. And at some point you may also think to yourself, “Am I actually hearing them say ‘Underwhelmed’, instead? Because that would be equally appropriate.” (Zing.)

At some point in this Tim Burton movie you may notice that the characters are calling their three-dimensional world “Underland” instead of the “Wonderland” you’re accustomed to. And at some point you may also think to yourself, “Am I actually hearing them say ‘Underwhelmed’, instead? Because that would be equally appropriate.” (Zing.)

I went to see this film because everyone else had seen it and I was sick of having to run off halfway through conversations at work with my hands over my ears shrieking, “I can’t hear you!” when idle chatting unexpectedly turned towards the plot. General consensus was that the movie was average. It’s not much hype: people will tell you a movie’s terrible and it is rarely as bad as you expect, or people will tell you a movie is excellent and it turns out to just be okay, but when everyone tells you something is meh, it’s usually pretty accurate. And in this case, it was.

With the misleading title of Alice in Wonderland, you would be forgiven for thinking Burton is recreating the story we’ve already seen once before in authentic Technicolor by some little-known company called Disney. In fact, what we have here is Alice’s story thirteen years later, when she is confronted in reality by an unpleasant situation and escapes from it to the world of her youth. Though this time around, she’s having a lot of trouble waking up.

Tim Burton keeps the nepotism going with Helena Bonham Carter playing the Red Queen as bobble-head toy. He also helps bestest pal Johnny Depp pay his bills by casting him as the Mad Hatter, which, of course, he does well, but frankly I am sick of the assumption that Depp is the only actor alive today who can put on a silly headpiece and an affected voice. Too much more like this and he is in danger of becoming a cuter version of Mike Myers, a comparison not helped by the Hatter’s occasional Shrek/Fat Bastard Sco’ish accent. Alice herself is played by Our Mia Wasikowska, who has been accused of appearing to be a crack addict but, as far as I can tell, is only at the mercy of the makeup artists just like everyone else, and her voice is entrancing. In other news, Little Britain’s Matt Lucas plays both Tweedledum and Tweedledee, underused and epic of face; king of stern Alan Rickman says “stupid girl” in an eerily Snape-like voice as the blue caterpillar; Crispin Glover is put on a stretching machine as Carter’s sidekick and Anne Hathaway drifts about with her hands aflutter as the White Queen. There are of course more cameos, and good ones too. The actors are not at fault for the movie: Burton always chooses well, and is lucky that his beloved wife is a good actress seeing as he casts her in everything he does. But the cast cannot lift this movie up from mediocrity.

I can’t quite define what is lacking here. I’ve always been fairly ambivalent towards Burton’s movies, in that I never hate them but can never quite understand the level of obsession some people have for him as a director. Alice is the same: not awful, but not brilliant. The score, by Danny Elfman, is fine. The costumes are quite lovely, especially Alice’s as she grows and shrinks. So as we follow our heroine through this world, trying to save her old friends from the Red Queen’s tyrannical rule, and we cheer her on, but not actually out loud. The theatre contained one of the quietest audiences I’ve ever been part of—and it was fairly full and IMAX-sized—because there wasn’t much to react to. It wasn’t funny, or scary, or anything. It just was.

Avatar, while being fairly crap, has done one thing to audiences: it has spoiled us in regards to visuals. If Alice in Wonderland had come out before Avatar, instead of the other way around, perhaps Tim Burton’s world would have stunned us more. As it is, James Cameron’s world was so captivating that 3D has to hit you upside the head with immersion to have an impact, and Alice did not. Burton’s beautiful use of colour—draining everything in the White Queen’s world, enriching it in the Red Queen’s, and making it blossom in the end credits—is always something to be admired, but still did not lift the movie.

For something that costs a fortune to see—we paid forty-four dollars, even before food—it doesn’t feel worth it. Unlike Avatar, it’s not necessary to see it 3D. Save your money now; hire it on DVD in a few months. It’s worth $5.95, surely, but $22.00? Not much is.

Two notes: one, don’t bother staying until the end of the credits, nothing happens; and two, it is one of the few things I’ve seen recently that passes the Bechdel Test. If anything, see it for that.

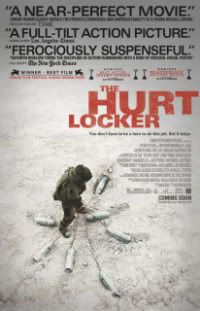

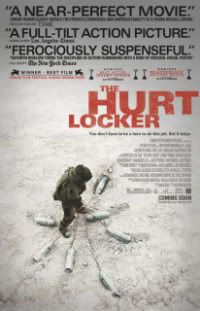

Sometimes there are movies where the reasons behind the titles are clear. Croupier, for example, is about a croupier. No surprise there. Kill Bill is about killing some flute player called William who talks at the speed of snail. Amelie is about a girl called Amelie. You see them and can leave the cinema happy that whoever decides on the title made the right choice.

Sometimes there are movies where the reasons behind the titles are clear. Croupier, for example, is about a croupier. No surprise there. Kill Bill is about killing some flute player called William who talks at the speed of snail. Amelie is about a girl called Amelie. You see them and can leave the cinema happy that whoever decides on the title made the right choice.

Then sometimes you leave a movie like The Hurt Locker and think to yourself, “What a great movie! Where is the bathroom? And where the hell did the title come from?” Not once is the phrase mentioned during the movie. John Hurt isn’t in it, nor a particularly significant locker. A consultation with the IMDB boards reveal that a hurt locker is somewhere you threaten to put people. As in, if your name is Inigo Montoya, and you’re standing in front of the person who killed your father, you’ll probably be putting them in a hurt locker. So there you go. Now you don’t have to wonder about it.

Not that you have much of a chance to. The Hurt Locker won seventy-eight Oscars for a reason. Whether it’s the best picture of the year is entirely subjective, but it’s better on the whole than Pocahontas-ripoff Avatar, though not better than the first fifteen minutes of Up. Still, it is an engrossing, tense and well-shot movie, and I have no qualms with it winning its seventy-eight Oscars.

As a rule, I hate war movies. Along with Westerns and Big Sappy Romances, I avoid them the best I can. Some suck me in, but generally I run far away from movies that involve blood, sweat, dust or tears. The Hurt Locker’s hype palled up with my excitement for the idea of a woman winning a Best Director Oscar for the first time, and there I was, stealing other people’s seats at the cinema so I could be closer to the screen and sucked in to this world.

Apparently it’s set in Iraq in 2004, though you’d never know the date (here I can’t help but mention the surfeit of anachronisms, like iPod touches and XBOX360s). William James has just joined the Bravo company’s bomb disposal squad after a brief cameo from previous team leader and excellent accent Guy Pearce as Matt Thompson. James is played by Jeremy Renner and is almost immediately shown as the kind of guy who thrives on risks and could be found in a B-grade movie yelling, “I don’t play by the rules, okay?” while their fellow team members scream, “You’re reckless!” He runs, not walks carefully, to bombs; throws smokescreen grenades without warning to his fellow team members; and takes off his bomb suit because it’s uncomfortable. His partners, by-the-book JT Sanborn and nest of fear Owen Eldridge, are less than pleased to have their lives treated so lightly, and so they should be.

But Bigelow’s strength lies in the fact that you don’t actually hate Renner. He’s there as a saviour, after all, and spends every assignment in what is essentially a suicide mission. He jokes and plays, does his job excellently, and is buddy-buddy with the local gangsta-talking ten-year-old DVD salesperson. He’s human, and for him, war is a drug. Disarming bombs is his fix.

The Hurt Locker, however, wasn’t quite as tense as I was led to believe. I wonder if it was because I went in imagining that in a movie about a bomb disposal unit, there was a chance that every character would die, and therefore didn’t invest myself in them as much as I usually do. I still cared for the characters, especially Eldridge, who was the most anxious about his job, his strengths, and his sanity, but I distanced myself from them.

Some unexpected star power in Ralph Fiennes, Evangeline Lilly and David Morse appear to remind us this isn’t a documentary, though the three team members have been around, but not entirely memorable for me until now. The movie is well-cast, beautifully shot, tense, gritty, and bloody. It manages to have less gore than you could expect for such a film bar one particularly upsetting scene regarding the disposal of a body bomb, and is probably the sweariest movie I’ve seen since the first three minutes of Four Weddings and a Funeral. It’s definitely a movie worth watching, as it does not glorify war as much as show how much it is deadly, terrifying, and able to alter the lives of soldiers irreparably.

After the blinding headache I received watching Mystic River, one of the most devastating movies plotwise I have ever seen, I baulked a little at seeing Shutter Island as it was penned by the same author. But it had a mental hospital on a deserted island and looked awfully creepy, so despite the two-and-a-half hour running time I couldn’t really resist. Well, that was back in September, and six months later the thing has finally arrived at cinemas, and was unable to live up to the hype I generated for it.

After the blinding headache I received watching Mystic River, one of the most devastating movies plotwise I have ever seen, I baulked a little at seeing Shutter Island as it was penned by the same author. But it had a mental hospital on a deserted island and looked awfully creepy, so despite the two-and-a-half hour running time I couldn’t really resist. Well, that was back in September, and six months later the thing has finally arrived at cinemas, and was unable to live up to the hype I generated for it.

The movie opens as Federal Marshal Teddy Daniels is on a ferry to Shutter Island, sent for a case involving a disappearing patient at the island’s prison for the criminally insane. Rachel Salondo drowned her three children and has, somehow, gone missing from her room. Can Daniels, along with his new partner Chuck, find Salondo? Does Teddy have ulterior motives for being on Shutter Island? Do the doctors have ulterior motives for getting Teddy onto Shutter Island?

The whole movie is rife with clues to what is really happening on this isolated island. A lot of them are red herrings, or confusing, and that is the ultimate problem: that when the ending arrives, it’s hard to buy. The longer I think about it, the more I feel that the movie didn’t lead there, but somewhere else altogether. In some movies, a second viewing gives you the thrill of rediscovering scenes that now appear in a completely different light. Whenever I reflect over Shutter Island’s scenes, I can only think, “But that makes absolutely no sense. What the hell?”

I doubt I’ll be watching it again to see if I’m right. For one, the music in this movie is laughably over-the-top. Perhaps it’s purposeful, but the ridiculously LOUD AND DRAMATIC VIOLINS as Teddy and Chuck and their delightfully ’50s-era nicknames drive up to a fence. The music makes it seem like perhaps zombies or vampires are going to jump out at you unexpectedly. (Spoiler: they do not.) It made me feel as if I’d just watched the climax of the movie in the first four minutes. That, along with some appalling green-screen work whenever Teddy finds himself in a moving car or boat or standing in front of some lush and distant scenery, makes it an awkwardly amateur film in those respects. From Martin Scorsese, no less. I imagined him standing in front of a CG computer and adjusting his glasses, saying to the digital artists, “What is this modern tomfoolery? In MY day, we didn’t have real forests, we had to make them out of clay and light them with fire we built with our own hands! Do that!”

Tempering the crappy effects and sounds was the fantastic acting. Leonardo DiCaprio played the Marshal himself, and spent most of the movie sucking on a lemon and looking angry. Mark Ruffled-o was much more endearing than he is playing romantic fodder in lightweight comedies, charming Leo and everyone else as the mellow and logical Chuck. The divine Ben Kingsley is Dr Cawley, the institution’s head psychiatrist and a man with a disarming smile and a good way of biting a pipe. Post-Rorschach Jackie Earle Haley appears briefly and is almost unidentifiable. (Perhaps he needed a moving mask?) My favourite was a surprising turn by Michelle Williams as Teddy’s wife Dolores, killed in an apartment fire, who appears to him pleading for his help, and is frankly brilliant as well as beautiful. These credible and beloved actors, along with some genuinely scary set pieces, save this from being terrible and elevate it to okay.

When a storm ravishes the island, you will feel like the rain is bearing down on you, too. When Teddy is scouring the prohibited, dark and ominous C-block for information, you will be scared. (Perhaps, like the one person in my crowded cinema, you’ll even shriek and thus cause the rest of the audience to start laughing.) When the music isn’t overbearing, the mood is exactly what Scorsese wants it to be.

Except for the ending. I can’t stop thinking about it. To me, if the ending is true, then the rest of the movie makes no sense. If the rest of the movie is true, then the ending makes no sense. It makes me want to pick up the original novel and figure out what author Dennis Lehane had in store for Teddy. Something about it smacks of cliché and other parts strike of stupid. And in more parts—like in an interrogation scene where someone is handed a glass of water but is holding nothing but air when she sips it—it just appears to be lazy filmmaking.

Go see it, just so we can discuss it. But if you really want a movie about what happens in a mental institution, hire Quills. At least that has Geoffrey Rush in the buff in it.

In early 2008 I was handed a copy of the book The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by a sales rep at work and told it was going to be the next big thing. I have heard this spouted before—about thirty-seven times a week for ten or so years—but this was the one time it was absolutely and utterly true. And unlike Harry Potter, I was there at the start, telling people about this new book and selling it without the power of 21 million books sold and three movies behind it like it has now. Sure, it’s a pathetic claim to fame, but in the bookselling world, you take what you get. (I had a ghastly-covered advance copy of Twilight once too, but alas had to give it back to the rep once I’d finished reading it. Now they’re selling on eBay for nearly two thousand dollars and I wish I had pretended to lose it.)

In early 2008 I was handed a copy of the book The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by a sales rep at work and told it was going to be the next big thing. I have heard this spouted before—about thirty-seven times a week for ten or so years—but this was the one time it was absolutely and utterly true. And unlike Harry Potter, I was there at the start, telling people about this new book and selling it without the power of 21 million books sold and three movies behind it like it has now. Sure, it’s a pathetic claim to fame, but in the bookselling world, you take what you get. (I had a ghastly-covered advance copy of Twilight once too, but alas had to give it back to the rep once I’d finished reading it. Now they’re selling on eBay for nearly two thousand dollars and I wish I had pretended to lose it.)