It has been a while since I’ve last posted here, but I promise I have a good excuse. On March 11—nearly a month ago now, lord—at some ridiculous time of the morning, I had a baby. Her name is Natalie Rocket and she is the cutest baby ever, and I’m not at all biased so you should take my word for that. Going to a cinema is a little tricky at the moment, but I’m hoping to head to some of those sessions you can take a baby to or head to the excellent Hoyts Victoria Gardens, whose cinema 2 has a crying room. I do, however, plan to let my kiddo be babysat for the first time when The Avengers comes out later this month, because I am in love with Captain America.

It has been a while since I’ve last posted here, but I promise I have a good excuse. On March 11—nearly a month ago now, lord—at some ridiculous time of the morning, I had a baby. Her name is Natalie Rocket and she is the cutest baby ever, and I’m not at all biased so you should take my word for that. Going to a cinema is a little tricky at the moment, but I’m hoping to head to some of those sessions you can take a baby to or head to the excellent Hoyts Victoria Gardens, whose cinema 2 has a crying room. I do, however, plan to let my kiddo be babysat for the first time when The Avengers comes out later this month, because I am in love with Captain America.

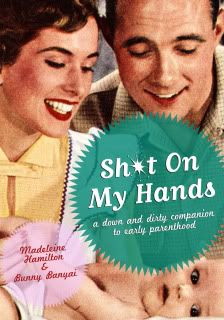

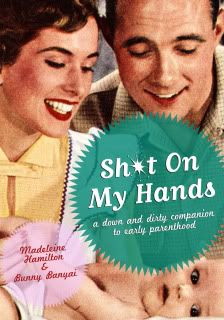

I can review something, however: a lovely friend gifted me a copy of the small in stature but big in larfs book Shit on My Hands, by Madeleine Hamilton and Bunny Banyai. It’s pocket (or handbag or nappybag) sized and it’s about those first few terrifying days, months and years after you pop out a sprog. And it’s not at all twee, not even in a retro way (though it does have some hilarious retro pictures with terrible of-its-time kid-based advertising that must have decimated the population in the 1930s.) It’s just funny. And accurate. And there are swear words in it. Which you need to read when you’re trying not to curse so much in front of your new offspring.

Some choice phrases that made me laugh out loud include: “After you become a parent the nightly news may as well be called ‘terrible things that could happen to your child’.” (Incidentally I now cry at almost any ad with a baby in it because hormones.) On pink: “The birth of a baby girl...[is] also likely to herald the arrival of so much pink paraphernalia it’ll look like a flamingo has thrown up in your hospital room.” (True, but then as I only bought her blue or green clothes at least she now has an assortment of colours.) On competitiveness between parents about who has slept the least: “ ‘Well, my baby woke every fifteen minutes. And she vomited all over her sheets. Then she rang the Department of Human Services to tell them I was an incompetent turkey, before registering herself for membership of the Fascist Youth League.’ ” Look, there’s a million more things that are probably funnier, but unless I take notes (which I do at movies, and if I’m paying attention with books I fold over page corners when interesting stuff happens, but don’t tell my primary school librarian that or she’ll throw chalk at me) I am not good at remembering things. Especially now that I no longer sleep in any normal sense of the word. But take my word for it: this book is funny, and probably would be even if you don’t have kids or even want them, because then you can laugh at the pain of others. And if that’s not what life is about, I don’t know what is.

I give this book five out of five cute babies in hats, because I was in the mood for a laugh and I got one and anything more complicated than that can be saved for when I can walk properly again.

I give this book five out of five cute babies in hats, because I was in the mood for a laugh and I got one and anything more complicated than that can be saved for when I can walk properly again.

Not at all the new Girl with the Dragon Tattoo like the press is desperately trying to pass it off as, Headhunters is completely different, both in plot, character, and feel—and it’s excellent fun. Thundering along at great speed and with a main character who will lose your affections at the start and then win you back, this is how crime movies should be made.

Not at all the new Girl with the Dragon Tattoo like the press is desperately trying to pass it off as, Headhunters is completely different, both in plot, character, and feel—and it’s excellent fun. Thundering along at great speed and with a main character who will lose your affections at the start and then win you back, this is how crime movies should be made.

Roger Brown (Aksel Hennie, incidentally the first person convicted for doing graffiti in Norway), as he explains in a brief voiceover at the start, is 1.68m tall and compensates for his lack of stature with an oversized house and his improbably beautiful and tall wife Diana (Synnøve Macody Lund), who, like a surprisingly number of people in crime books (this is adapted from Jo Nesbø’s book of the same name) but not in reality, runs an art gallery. He’s a headhunter, a recruitment agent who knows the value of reputation. He’s good at his job and makes a pack of money, but not enough to fund the lifestyle that he and Diana lead. To compensate, and with the help of his security company cohort Ove (Eivind Sander), he also moonlights an art thief more than happy to steal from the clients he’s hiring, and whose personal information it is ridiculously easy to discover when you’re the one doing the interviewing. Despite this, Roger’s finances are precarious and his emotionless affair with brunette Lotte (Julie Ølgaard) is coming to an end when he encounters the man who could change his life: Clas Greve (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, almost ridiculously handsome), the perfect candidate for the job Roger is hiring for, and someone who’s just inherited an original Rubens. Clas, alas, is not your everyday job hunter.

Roger is a total prong, and when everything in his life falls to shit you’re almost pleased—at first. Slowly, Roger regains your compassion and becomes a character you can get behind instead of one you want to push over, and kudos to Aksel Hennie (who has a bit of a Steve Buscemi look to him) for portraying a character arc you’re initially unwilling to follow. Part of this is the ridiculous situations it doesn’t take long for him to be in—you’ll probably want to cover your eyes for a particular hiding place he chooses, and for a fight he has with a dog—and part of it is his reactions, which don’t have you shouting at the screen “Augh! Why are you doing this?” but rather thinking: yes, that is the right thing to do. He’s a smart guy, just confused about his huge ego fighting with his lack of self-esteem. The characters that surround him are excellent too: Diana is lovely and misinterpreted, Clas ominous in his smoky expression, Ove hilarious in his introduction as he runs around his house naked shooting pop guns at a giggling Russian prostitute. Even the peripheral characters, including overweight identical twin police officers, and real-life police chiefs at a press conference, are wonderful touches that make this movie a cut above other action-type flicks.

The movie doesn’t pass the Bechdel Test—and the few women in it aren’t at all simpering, but are still being used by men in some way. Having said that, the men are all jerks. It’s also a bit gory in parts, which isn’t necessarily a criticism but something to point out if you’ve got a weak stomach for such things. (A brief pan over someone’s crushed face is followed by a solid close-up you weren’t expecting; also, the aforementioned hiding and dog scenes.) There’s a discrepancy at the end that I haven’t quite figured out, but as I went to see it alone, I don’t have anyone to set me straight.

Those are all very, very minor gripes in a movie I genuinely adored. Go see it; it’s a thrilling, entertaining crime adventure that deserves a wider release than it will probably get, and equal, if not more hype, to the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (which, as possibly an in-joke, Diana is actually watching the Swedish version of at one point.) I give it eighteen out of twenty machine gun bullets scattered on the ground.

Before I’d even seen this movie, I’d seen enough previews for it that I’d planned the review in my head. I was going to draw a comic which had three stick figures and went something like: THREE GUYS HAVE A WEIRD THING HAPPEN (picture of figures next to whatever gave them powers), GET POWERS (picture of them freaking out, waving their little stick arms), EVERYTHING IS FUN (picture of them doing fun thing), OH NO IT ALL WENT HORRIBLY WRONG WHAT A SHOCK (picture of them all dead with crosses for eyes). And look, my prediction wasn’t far off, because I have been to movies more than three times in my life and I know how these things go. But instead of cursing you all with my awful drawing skills, I’m actually going to give this a proper review, because it deserves one.

Before I’d even seen this movie, I’d seen enough previews for it that I’d planned the review in my head. I was going to draw a comic which had three stick figures and went something like: THREE GUYS HAVE A WEIRD THING HAPPEN (picture of figures next to whatever gave them powers), GET POWERS (picture of them freaking out, waving their little stick arms), EVERYTHING IS FUN (picture of them doing fun thing), OH NO IT ALL WENT HORRIBLY WRONG WHAT A SHOCK (picture of them all dead with crosses for eyes). And look, my prediction wasn’t far off, because I have been to movies more than three times in my life and I know how these things go. But instead of cursing you all with my awful drawing skills, I’m actually going to give this a proper review, because it deserves one.

Chronicle opens with high school senior Andrew (Dane DeHaan, appropriately sulky and gawky) setting up his new video camera to record his life: his physically abusive, alcoholic father; his dying mother, strapped to machines in her bed; his school life, where bullies torment him mercilessly and the only person who gives him any time is his philosophical-stoner cousin, Matt (Alex Russell). Andrew doesn’t do himself any favours by bringing a video camera to school and creeping everyone out—in fact, he’s generally unlikeable, but wholly sympathetic regardless—but it comes in handy when, at a warehouse party, he’s summoned by Matt and the school’s gosh-darn endearing Mr Popularity Steve (Michael B Jordan) to a strange hole in the ground. They go underground, the camera gets fuzzy, things are weird, then bam: they are back in the sunlight and suddenly the three of them have developed telekinetic powers. All right! Awesome! This could never go wrong!

The movie succeeds because the three do exactly what you (well, I) would do if you had telekinetic powers. There’s a nod to the Lego video game franchise as they build things with their mind; they skim rocks over rivers; they use a leaf blower to blow up the skirts of the pretty girls. (Hey, I didn’t say they were mature about it.) They start small as they learn to control their powers, and the three develop a close bond—but it doesn’t take long before a harmless prank gets dangerously close to a fatality and the three lay down some ground rules, including the most important: don’t use the powers when you’re angry. However, teenagers do angry really well, and when things go wrong, it happens on an epic scale.

The movie centres around Andrew, as the one with the camera, but all three characters feel convincing: they dress and act like normal people, are occasionally jerks and frequently humane. Matt’s squirm-worthy attempts to prove to a girl that he’s, like, cool, but, like, above being like popular and stuff are painfully endearing; Steve’s determination to be a good politician see him take on Andrew as a challenge, where they use their powers to gain him popularity in the most wholesome way possible. Even Andrew’s jerk of a father has some depth: you hate him, but you have some understanding of him. This, all told in what is essentially a found-footage film (though both Chris and I had thought of the phrase “lost-footage”, as the movie uses footage from cameras that are destroyed, CCTV footage, people’s iPads and so on) is very impressive; it even dodges the problem of Andrew never being on camera when he gets the idea to control it with his mind so it is always looking at the scene from a short distance. The special effects are faultless, which makes the movie’s many tricks—small or large—great fun. The boys never break from character, and Chronicle tracks in an hour and a half the path to villainy that George Lucas barely achieved in the first (second?) three Star Wars movies.

Chronicle doesn’t pass the Bechdel Test—there are women, but they never talk to each other—and you do occasionally want to take Andrew by the ear and get him to the counsellor’s office for a thorough discussion about emotional control and dealing with turmoil at home (and finding somewhere new to live—or a way to get his father in jail.) But on the whole, Chronicle is a surprisingly excellent film that doesn’t bother too much with the why of getting superpowers (because really, who cares?) as much as what kind of person you are, and how you deal with them when you have them.

I give it four out of five car rides to school.

Like the birthday kid at a swimming party, you’re thrown in in the deep end of this head-scratching psychological thriller and left to flail about helplessly for about the first half hour before someone throws you a flotation device, but even then, it’s maybe the equivalent of three ping-pong balls rather than a lifejacket. What this does have at the start is a brylcreemed Robert Ledgard (Antionio Banderas), craniofacial plastic surgeon extraordinaire who lives in a sprawling Spanish estate; Vera Cruz (Elena Anaya), a beautiful woman who wanders around a sparsely furnished room wearing nothing but a body stocking; and a house full of servants who seem totally at ease with the fact that Robert has a woman locked in a room in his house. Why she is there, why Robert has video cameras in her room that feed into his wall-sized television and why Marilia (Marisa Paredes)—his longtime housekeeper—is so complicit in the captivity so badly is the soul of the story, told back and forth in time from the death of Robert’s wife up to the present (actually the future, as it’s set in February 2012.)

Like the birthday kid at a swimming party, you’re thrown in in the deep end of this head-scratching psychological thriller and left to flail about helplessly for about the first half hour before someone throws you a flotation device, but even then, it’s maybe the equivalent of three ping-pong balls rather than a lifejacket. What this does have at the start is a brylcreemed Robert Ledgard (Antionio Banderas), craniofacial plastic surgeon extraordinaire who lives in a sprawling Spanish estate; Vera Cruz (Elena Anaya), a beautiful woman who wanders around a sparsely furnished room wearing nothing but a body stocking; and a house full of servants who seem totally at ease with the fact that Robert has a woman locked in a room in his house. Why she is there, why Robert has video cameras in her room that feed into his wall-sized television and why Marilia (Marisa Paredes)—his longtime housekeeper—is so complicit in the captivity so badly is the soul of the story, told back and forth in time from the death of Robert’s wife up to the present (actually the future, as it’s set in February 2012.)

I wouldn’t dare spoiler anything for you, but be assured the horror of the story—and you will be horrified—has little to do with the new, resilient skin that Robert is experimenting with and more to do with the horrendous acts people commit. If you aren’t in a position to deal with sexual assault on film, stay far away from this one. Not only are the scenes convincingly awful, as the experience must be, but the confusion surrounding them can make for an uncomfortable viewing. I’m loathe to say more and ruin the movie, which held countless surprises, but there you have it. It touches on a few sex/gender issues as well, which Pedro Almodovar has done in the past. Having a director out there game to try some new stuff is great, but I guess I feel a little out of my depth in commenting too much on it.

So, onto things I know! I know I generally love Antonio but found him completely alarming in this film; I know that the acting was amazing from everyone. Almodovar is adept at getting nuances out of actors who get offered Western roles that aren’t quite as meaty (Penelope Cruz, for example, is excellent in Volver but more popular in the fourth Pirates of the Caribbean movie, where everyone is required to be melodramatic) so seeing Banderas in a role where he wasn’t likeable was hard—because usually he’s so lovely in them—but also impressive. The choppy narrative style was an interesting route to take and, luckily, fell on the side of compelling instead of annoying (though I probably annoyed everyone around me by whispering my confusion at Chris every five minutes.) It was a very narrowly landscaped film—we get a feel for Ledgard’s home but not the environment around it, and only a few other settings, which means it doesn’t feel particularly Spanish (apart from the fact that it’s in Spanish and subtitled) and instead feels appropriately claustrophobic.

It’s a confronting, engaging, revenge-driven flick filled with relationships you’re continually unsure of. Who do you hate? Where does the right of revenge end? Why do people ask rhetorical questions anyway? Well, perhaps I’ll stop and just rate it something high like eight out of ten tiger stripes.

As requested by the lovely Afsana

The ten-minute introduction to the movie Hugo, before the title card even reminds you what you’re at the cinema to see, is an absolute popcorn-gobbling delight of special effects. As we follow the titular hero through the labyrinthine pathways that make up the landscape of his home—living behind the walls at a Parisian train station—we pass through cogs and pendulums and down slides and up rickety stairs, all merging seamlessly together to create an entirely new and beautiful world. Seeing this in 3D is even more incredible, and is an immediate way to engage your audience so that they’re staring slack-jawed with glee within moments.

The ten-minute introduction to the movie Hugo, before the title card even reminds you what you’re at the cinema to see, is an absolute popcorn-gobbling delight of special effects. As we follow the titular hero through the labyrinthine pathways that make up the landscape of his home—living behind the walls at a Parisian train station—we pass through cogs and pendulums and down slides and up rickety stairs, all merging seamlessly together to create an entirely new and beautiful world. Seeing this in 3D is even more incredible, and is an immediate way to engage your audience so that they’re staring slack-jawed with glee within moments.

The world of young boy Hugo (Asa Butterfield) himself is not so lovely. It’s 1931, and, orphaned after the death of his clockmaker father (Jude Law) in a museum fire and sent to live with his alcoholic uncle, his life goes from quiet contentment to ruination. Unable to go to school, running the station’s clocks is his only job, but one he must do perfectly in case anyone notices that as the movie begins, he is now alone, his uncle having abandoned him. Apart from the clocks, Hugo spends his time tending to a broken automaton his father found in a museum, trying to find parts for it—or to steal them from the station’s toymaker, Papa Georges (Ben Kingsley) out of view of the orphan-catching Station Inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen). After an altercation with Georges that sees him lose his father’s notebook, a precious memento that also holds the clues to fixing the writing-robot that is his father’s only legacy, he thinks all is doomed. But wait! Because it’s an adventure story (and a self-referential one at that), an effervescent girl named Isabelle (Chloe Grace Moretz, adorable) is waiting in the wings to befriend him, even though her guardian is Georges himself. And between them, they may just hold the not entirely metaphorical key to everyone’s angst—Hugo’s emotional and mechanical problems, and the secret her godfather has been keeping for years.

Hugo is a love letter to cinema itself: not only in its visuals, but in the subject matter and in the characters themselves. Hugo’s father adored cinema and took his son to films, whereas Georges has never let Isabelle see a movie in her life. There is a glorious line to make all movie-lovers sigh, as Hugo tells Isabelle about the first time his father had seen a movie: “He said it was like seeing his dreams in the middle of the day.” The history of film is touched on as well, as the first one shown—a train pulling into a station—causes the entire audience to shriek and run as the train barrels towards the camera. Connected to it all is cinematic genius Georges Melies, whom you might remember from a particularly referenced and adored film scene where the moon cops a rocket to the eye. Any movie about movies is one that floats my boat, and this is lovingly rendered in every way, where the recreations of hundred-year-old special effects still have the power to amaze, and the loss of film can cause the loss of much more personally.

Quirky French touches abound, as the station’s other occupants—flower-seller Lisette (Emily Mortimer), the object of the Station Inspector’s awkward affections; cafe owner Madame Emile (Frances de la Tour, one of three Harry Potter actors in the film—she played the French giantess); and newspaperman Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths, second Potter-person, Uncle Vernon) dance around each other and create a lightness and sweetness that the movie’s occasionally sad moments need. Moretz is a delight as an enthusiastic counterpart to Butterfield’s quiet grimness, and Cohen does a wonderful job making the initially dastardly Inspector a sympathetic character (it does take a while to warm to the man, though. What kind of jerk throws orphans in a cage?)

However I couldn’t really bond with Hugo himself, a character with a genuinely sorrowful backstory but who in Butterfield was unable to sell me on any of his emotions or the reasoning behind some of his actions. Sadly, this made him one of the least interesting characters in the movie for me. Papa Georges’ backstory, while interesting and visually entrancing, is not quite enough payoff for the build-up surrounding it—so I enjoyed the movie but still left the theatre feeling slightly unfulfilled. I do recall feeling the same way when I read the book as well: that I was hoping for a dramatic reveal and was underwhelmed. Characters frequently did the frustrating trope where they don’t explain their actions, choosing silence over logical discussion and making the movie stretch out into devastation when it could have been remedied by a nice chat over a cup of tea.

But it’s still a fun film, and kudos to director Martin Scorsese for doing to 3D what the mechanically brilliant young Hugo does to a mechanical mouse—injecting it with something new and wonderful. I give it eight out of twelve o’clock.

In Australia, Hugo is released January 12.

David Fincher: he’s great, isn’t he? The Social Network was one of my favourite movies of recent years and he also made this little-known flick called Fight Club that you can’t mention in a sentence without everyone in the vicinity falling over themselves to sputter out their adoration of. He’s a talented director who knows how to craft addictive movies with an original edge.

David Fincher: he’s great, isn’t he? The Social Network was one of my favourite movies of recent years and he also made this little-known flick called Fight Club that you can’t mention in a sentence without everyone in the vicinity falling over themselves to sputter out their adoration of. He’s a talented director who knows how to craft addictive movies with an original edge.

So why, oh lord why, did he choose to remake Niels Arden Oplev’s Swedish film that was perfectly capable of telling the story already? Why did he waste months and years of his precious filmmaker time to give everyone a third outing of the Millennium Trilogy? 30 million people worldwide have read the books; the first film made over a hundred million smackers. This is not some obscure gem that needed a fresh facelift: it’s all tremendously modern and already available in literary and film formats. So the question is: what did Fincher hope to achieve with his version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and did he succeed? He claims that it is a completely different film from the Swedish version, but it’s not, of course. When they both work off the same source material, a dense brick of a novel with elaborate backgrounds for each character and incident, they are going to hit the same beats. Yes, it is different, because someone different directed it and the actors are different. Yes, it’s different because everyone speaks in English with Swedish accents (though they read Swedish-language newspapers.) But honestly, apart from a small change in the ending, it is the same film told the same way, and you’ll feel exactly the same by the end as you would at the end of the Swedish version. (That is: paranoid about government agencies, horrified by all men and never able to have sex again.)

It’s hard to see past that to judge the film on its own merits. Of course, it’s wonderfully cast: Rooney Mara captured the damaged (and thin) look wonderfully to be computer hacker/ward of the state Lisbeth Salander; Daniel Craig is the perfect age to be disgraced but excellent investigative journalist Mikael Blomkvist; and Christopher Plummer is expansively patriarchal as Henrik Vanger, the wealthy industrialist who inadvertently brings the two together to solve a forty-year-old crime: the loss of his beloved niece. It’s not all Agatha Christie innocence, however: you will be disturbed, by the outcome and also by many scenes disturbing in both sexual and non-sexual gore (Lisbeth’s relationship with her new guardian Bjurman—Yorick van Wageningen—is especially something you’ll want to cover your eyes for.) The growing friendship between youthful Salander and craggy Blomkvist is convincing and enjoyable to witness; the peripheral characters are portrayed just about as you’d imagine them. On a visual level, Fincher perhaps overtakes Oplev purely because where Oplev sees the place he lives and conveys it in a natural way, Fincher sees it from our non-Swedish perspective, revealing the white, icy beauty and Ikea-white angles of homes and buildings. His intro, also, is quite mind-blowing, as a soft, tender tinkly piano barrels into a tar and sweat-soaked Karen O intro as Mara and Craig sex things up in an edgy, oiled-up way along with an eagle, a snake, and some raunchy flowers. Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor score the whole flick with requisite rage and gentleness.

Lisbeth’s use of Google and Wikipedia to track someone down seems to undermine her enormous talent in the hacking field; the Swedish accents sometimes slip; I felt that despite the epic running time—nearly three hours—Lisbeth’s storyline was not given enough time; during a Eureka moment for Blomkvist he makes such a ridiculous show of taking off his glasses in mute shock it seemed like a cliché in what is otherwise a very cliché-free movie; and in frustratingly Hollywood way of thinking, female Rooney is given countless crotch shots and appears fully naked frequently while male Blomkvist (who is polyamorous and hardly a prude) reveals his chest and the barest hint of butt-crack.

Still, these facts don’t at all ruin the film. Fincher’s use of actors in their natural, often makeup-free state is commendable (and something I enjoyed about the first movie trilogy); the long running time doesn’t mean the movie drags—it’s enthralling from start to finish; Mara’s Salander, like Noomi Rapace in the Swedish version, is an absolute treat of a character, scarred from a lifetime of people screwing her over but with a raspy charm all her own: wearing a t-shirt saying “Fuck you you fucking fuck”, explaining Blomkvist’s background to the man who has hired her: “Sometimes he performs cunnilingus. Not often enough in my opinion”—she really is amazing and is the new style of heroine everyone says she is. It passes the Bechdel Test (barely) and, in Sweden, is called Men who Hate Women, so the women are smart and not underwritten.

By all means, go see it if you’re unable to see the Swedish version—it’s a well-crafted film telling a wholly interesting and grotesque family crime story. But without it showing me anything new about the story (which admittedly, I have possibly overdosed on), it is still a vaguely pointless exercise. Because of this, and my clear ragey bias about it, I’m not going to give this movie a rating. See it for yourselves and let me know what you think.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is out January 12.

Attack the Block begins with a bunch of teenage miscreants mugging a young woman named Sam (Jodie Whittaker) at knifepoint in the a London street. During the altercations, an alien shoots from the sky, whereupon the kids beat the thing to death then parade it around on a stick. At this point, you’re pretty much thinking, great, I hope this alien’s friends fly down and kick the shit out of all these kids and claim the tall flats they live in as their base. I, for one, welcomed our new alien overlords.

Attack the Block begins with a bunch of teenage miscreants mugging a young woman named Sam (Jodie Whittaker) at knifepoint in the a London street. During the altercations, an alien shoots from the sky, whereupon the kids beat the thing to death then parade it around on a stick. At this point, you’re pretty much thinking, great, I hope this alien’s friends fly down and kick the shit out of all these kids and claim the tall flats they live in as their base. I, for one, welcomed our new alien overlords.

But then you end up following these kids through their incompetent attempts to defeat the sudden influx of aliens and, dammit, after a while you don’t want them to die after all. Led by moodily attractive teenager Moses (John Boyega), the gang come across as quite threatening to begin with until you realise that actually they are all pretty incompetent because they are, well, yoof. It’s Guy Fawkes Night, and they were out to create havoc and striving to be part of the gang led by the block’s main criminal mastermind, Hi-Hatz (Jumayn Hunter). Just as they finally strike it lucky enough to actually be on their path to, well, jail, more aliens rain down on them and everything changes, seeing the gang on the wrong side of everyone, from the police to Hi-Hatz to an irate Sam.

Having kids be the protagonists for a horror/sci-fi movie is pretty interesting, especially when director Joe Cornish chooses to be open about the facts that not all accidental alien-hunters are going to be as skilled as the team from Predators. These are kids who don’t have guns or fighting skills, but instead heed the call to arms with baseball bats, firecrackers, kitchen knives and false bravado. When shit gets real and they finally twig that they’re out of their depth, they can’t call for help because they’ve all run out of mobile phone credit; when they speed down staircases on their pushbikes they inevitably crash into the ground because they are not bicycle parkour enthusiasts. Despite the fact that the majority live quite standard home lives, getting told off by their mothers or told to keep out of trouble by their nannas, they’re all too desperately rough to turn to the grown-ups when being chased by deadly critters. And that’s the other thing, with them being kids: even though the movie is kind of funny, it’s not a balls-out comedy which makes it all the more surprising when you realise that not all of the teenagers are going to live out the film.

The film briefly touches on the state of British youth, when Moses speculates that the aliens have been sent by the Feds to kill the African-British because “we’re not killing each other fast enough”. It’s a nice try, but the fact that the kids, apart from Moses himself, seem to have fairly happy upbringings and some kind of self-awareness of what they’re getting into, means the movie doesn’t go far enough down that path, and you’re not even sure if any of the gang have learned a lesson by the end of it.

Nice touches are the aliens themselves: neon-fanged black holes of colour with no depth, like an orang-utan shagged a yeti in a dark cupboard using a glow-in-the-dark condom with a hole in it. The idea that colour shading would be different on a different hadn’t occurred to me and I thought it was really interesting, to be honest; it makes them shadowy and creepy even when they’re in a brightly-lit flat. It isn’t laugh-a-minute funny (which, as it’s from the writer of Hot Fuzz and stars Nick Frost, I was expecting), but it’s pretty amusing and the dialogue between the kids (who are also great actors) can be pretty hilarious at times. The two nine-year-old boys looking up to the gang are probably the comedy relief, flinging around tough phrases in high-pitched voices. It passes the Bechdel Test and the women in it—Sam, an elderly neighbour, and the girls the gang are all interested in—are pretty kick-ass, either physically or verbally.

Nick Frost’s high billing probably has to do with his star power more than his subdued role as a stoner in the only “safe house” in the building, though he and befringed try-hard Brewis (Luke Treadaway) smoke their way through some fairly funny moments. It was a fun movie that somehow missed a vital point with me, though I can’t think exactly what; I’d recommend it happily, even though it wasn’t quite cranked up all the way on either the funny, poignant, sci-fi or horror dials.

I give Attack the Block seven out of ten rows of glowing teeth. Because rows of teeth are SCARY.

It has been a while since I’ve last posted here, but I promise I have a good excuse. On March 11—nearly a month ago now, lord—at some ridiculous time of the morning, I had a baby. Her name is Natalie Rocket and she is the cutest baby ever, and I’m not at all biased so you should take my word for that. Going to a cinema is a little tricky at the moment, but I’m hoping to head to some of those sessions you can take a baby to or head to the excellent Hoyts Victoria Gardens, whose cinema 2 has a crying room. I do, however, plan to let my kiddo be babysat for the first time when The Avengers comes out later this month, because I am in love with Captain America.

It has been a while since I’ve last posted here, but I promise I have a good excuse. On March 11—nearly a month ago now, lord—at some ridiculous time of the morning, I had a baby. Her name is Natalie Rocket and she is the cutest baby ever, and I’m not at all biased so you should take my word for that. Going to a cinema is a little tricky at the moment, but I’m hoping to head to some of those sessions you can take a baby to or head to the excellent Hoyts Victoria Gardens, whose cinema 2 has a crying room. I do, however, plan to let my kiddo be babysat for the first time when The Avengers comes out later this month, because I am in love with Captain America. I give this book five out of five cute babies in hats, because I was in the mood for a laugh and I got one and anything more complicated than that can be saved for when I can walk properly again.

I give this book five out of five cute babies in hats, because I was in the mood for a laugh and I got one and anything more complicated than that can be saved for when I can walk properly again.