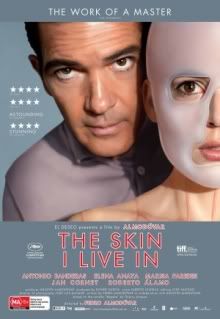

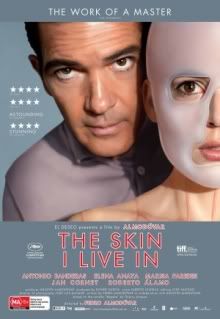

Like the birthday kid at a swimming party, you’re thrown in in the deep end of this head-scratching psychological thriller and left to flail about helplessly for about the first half hour before someone throws you a flotation device, but even then, it’s maybe the equivalent of three ping-pong balls rather than a lifejacket. What this does have at the start is a brylcreemed Robert Ledgard (Antionio Banderas), craniofacial plastic surgeon extraordinaire who lives in a sprawling Spanish estate; Vera Cruz (Elena Anaya), a beautiful woman who wanders around a sparsely furnished room wearing nothing but a body stocking; and a house full of servants who seem totally at ease with the fact that Robert has a woman locked in a room in his house. Why she is there, why Robert has video cameras in her room that feed into his wall-sized television and why Marilia (Marisa Paredes)—his longtime housekeeper—is so complicit in the captivity so badly is the soul of the story, told back and forth in time from the death of Robert’s wife up to the present (actually the future, as it’s set in February 2012.)

Like the birthday kid at a swimming party, you’re thrown in in the deep end of this head-scratching psychological thriller and left to flail about helplessly for about the first half hour before someone throws you a flotation device, but even then, it’s maybe the equivalent of three ping-pong balls rather than a lifejacket. What this does have at the start is a brylcreemed Robert Ledgard (Antionio Banderas), craniofacial plastic surgeon extraordinaire who lives in a sprawling Spanish estate; Vera Cruz (Elena Anaya), a beautiful woman who wanders around a sparsely furnished room wearing nothing but a body stocking; and a house full of servants who seem totally at ease with the fact that Robert has a woman locked in a room in his house. Why she is there, why Robert has video cameras in her room that feed into his wall-sized television and why Marilia (Marisa Paredes)—his longtime housekeeper—is so complicit in the captivity so badly is the soul of the story, told back and forth in time from the death of Robert’s wife up to the present (actually the future, as it’s set in February 2012.)

I wouldn’t dare spoiler anything for you, but be assured the horror of the story—and you will be horrified—has little to do with the new, resilient skin that Robert is experimenting with and more to do with the horrendous acts people commit. If you aren’t in a position to deal with sexual assault on film, stay far away from this one. Not only are the scenes convincingly awful, as the experience must be, but the confusion surrounding them can make for an uncomfortable viewing. I’m loathe to say more and ruin the movie, which held countless surprises, but there you have it. It touches on a few sex/gender issues as well, which Pedro Almodovar has done in the past. Having a director out there game to try some new stuff is great, but I guess I feel a little out of my depth in commenting too much on it.

So, onto things I know! I know I generally love Antonio but found him completely alarming in this film; I know that the acting was amazing from everyone. Almodovar is adept at getting nuances out of actors who get offered Western roles that aren’t quite as meaty (Penelope Cruz, for example, is excellent in Volver but more popular in the fourth Pirates of the Caribbean movie, where everyone is required to be melodramatic) so seeing Banderas in a role where he wasn’t likeable was hard—because usually he’s so lovely in them—but also impressive. The choppy narrative style was an interesting route to take and, luckily, fell on the side of compelling instead of annoying (though I probably annoyed everyone around me by whispering my confusion at Chris every five minutes.) It was a very narrowly landscaped film—we get a feel for Ledgard’s home but not the environment around it, and only a few other settings, which means it doesn’t feel particularly Spanish (apart from the fact that it’s in Spanish and subtitled) and instead feels appropriately claustrophobic.

It’s a confronting, engaging, revenge-driven flick filled with relationships you’re continually unsure of. Who do you hate? Where does the right of revenge end? Why do people ask rhetorical questions anyway? Well, perhaps I’ll stop and just rate it something high like eight out of ten tiger stripes.

As requested by the lovely Afsana

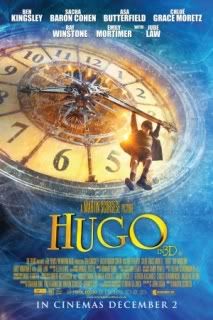

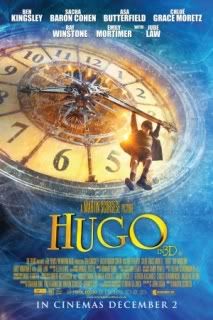

The ten-minute introduction to the movie Hugo, before the title card even reminds you what you’re at the cinema to see, is an absolute popcorn-gobbling delight of special effects. As we follow the titular hero through the labyrinthine pathways that make up the landscape of his home—living behind the walls at a Parisian train station—we pass through cogs and pendulums and down slides and up rickety stairs, all merging seamlessly together to create an entirely new and beautiful world. Seeing this in 3D is even more incredible, and is an immediate way to engage your audience so that they’re staring slack-jawed with glee within moments.

The ten-minute introduction to the movie Hugo, before the title card even reminds you what you’re at the cinema to see, is an absolute popcorn-gobbling delight of special effects. As we follow the titular hero through the labyrinthine pathways that make up the landscape of his home—living behind the walls at a Parisian train station—we pass through cogs and pendulums and down slides and up rickety stairs, all merging seamlessly together to create an entirely new and beautiful world. Seeing this in 3D is even more incredible, and is an immediate way to engage your audience so that they’re staring slack-jawed with glee within moments.

The world of young boy Hugo (Asa Butterfield) himself is not so lovely. It’s 1931, and, orphaned after the death of his clockmaker father (Jude Law) in a museum fire and sent to live with his alcoholic uncle, his life goes from quiet contentment to ruination. Unable to go to school, running the station’s clocks is his only job, but one he must do perfectly in case anyone notices that as the movie begins, he is now alone, his uncle having abandoned him. Apart from the clocks, Hugo spends his time tending to a broken automaton his father found in a museum, trying to find parts for it—or to steal them from the station’s toymaker, Papa Georges (Ben Kingsley) out of view of the orphan-catching Station Inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen). After an altercation with Georges that sees him lose his father’s notebook, a precious memento that also holds the clues to fixing the writing-robot that is his father’s only legacy, he thinks all is doomed. But wait! Because it’s an adventure story (and a self-referential one at that), an effervescent girl named Isabelle (Chloe Grace Moretz, adorable) is waiting in the wings to befriend him, even though her guardian is Georges himself. And between them, they may just hold the not entirely metaphorical key to everyone’s angst—Hugo’s emotional and mechanical problems, and the secret her godfather has been keeping for years.

Hugo is a love letter to cinema itself: not only in its visuals, but in the subject matter and in the characters themselves. Hugo’s father adored cinema and took his son to films, whereas Georges has never let Isabelle see a movie in her life. There is a glorious line to make all movie-lovers sigh, as Hugo tells Isabelle about the first time his father had seen a movie: “He said it was like seeing his dreams in the middle of the day.” The history of film is touched on as well, as the first one shown—a train pulling into a station—causes the entire audience to shriek and run as the train barrels towards the camera. Connected to it all is cinematic genius Georges Melies, whom you might remember from a particularly referenced and adored film scene where the moon cops a rocket to the eye. Any movie about movies is one that floats my boat, and this is lovingly rendered in every way, where the recreations of hundred-year-old special effects still have the power to amaze, and the loss of film can cause the loss of much more personally.

Quirky French touches abound, as the station’s other occupants—flower-seller Lisette (Emily Mortimer), the object of the Station Inspector’s awkward affections; cafe owner Madame Emile (Frances de la Tour, one of three Harry Potter actors in the film—she played the French giantess); and newspaperman Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths, second Potter-person, Uncle Vernon) dance around each other and create a lightness and sweetness that the movie’s occasionally sad moments need. Moretz is a delight as an enthusiastic counterpart to Butterfield’s quiet grimness, and Cohen does a wonderful job making the initially dastardly Inspector a sympathetic character (it does take a while to warm to the man, though. What kind of jerk throws orphans in a cage?)

However I couldn’t really bond with Hugo himself, a character with a genuinely sorrowful backstory but who in Butterfield was unable to sell me on any of his emotions or the reasoning behind some of his actions. Sadly, this made him one of the least interesting characters in the movie for me. Papa Georges’ backstory, while interesting and visually entrancing, is not quite enough payoff for the build-up surrounding it—so I enjoyed the movie but still left the theatre feeling slightly unfulfilled. I do recall feeling the same way when I read the book as well: that I was hoping for a dramatic reveal and was underwhelmed. Characters frequently did the frustrating trope where they don’t explain their actions, choosing silence over logical discussion and making the movie stretch out into devastation when it could have been remedied by a nice chat over a cup of tea.

But it’s still a fun film, and kudos to director Martin Scorsese for doing to 3D what the mechanically brilliant young Hugo does to a mechanical mouse—injecting it with something new and wonderful. I give it eight out of twelve o’clock.

In Australia, Hugo is released January 12.

David Fincher: he’s great, isn’t he? The Social Network was one of my favourite movies of recent years and he also made this little-known flick called Fight Club that you can’t mention in a sentence without everyone in the vicinity falling over themselves to sputter out their adoration of. He’s a talented director who knows how to craft addictive movies with an original edge.

David Fincher: he’s great, isn’t he? The Social Network was one of my favourite movies of recent years and he also made this little-known flick called Fight Club that you can’t mention in a sentence without everyone in the vicinity falling over themselves to sputter out their adoration of. He’s a talented director who knows how to craft addictive movies with an original edge.

So why, oh lord why, did he choose to remake Niels Arden Oplev’s Swedish film that was perfectly capable of telling the story already? Why did he waste months and years of his precious filmmaker time to give everyone a third outing of the Millennium Trilogy? 30 million people worldwide have read the books; the first film made over a hundred million smackers. This is not some obscure gem that needed a fresh facelift: it’s all tremendously modern and already available in literary and film formats. So the question is: what did Fincher hope to achieve with his version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and did he succeed? He claims that it is a completely different film from the Swedish version, but it’s not, of course. When they both work off the same source material, a dense brick of a novel with elaborate backgrounds for each character and incident, they are going to hit the same beats. Yes, it is different, because someone different directed it and the actors are different. Yes, it’s different because everyone speaks in English with Swedish accents (though they read Swedish-language newspapers.) But honestly, apart from a small change in the ending, it is the same film told the same way, and you’ll feel exactly the same by the end as you would at the end of the Swedish version. (That is: paranoid about government agencies, horrified by all men and never able to have sex again.)

It’s hard to see past that to judge the film on its own merits. Of course, it’s wonderfully cast: Rooney Mara captured the damaged (and thin) look wonderfully to be computer hacker/ward of the state Lisbeth Salander; Daniel Craig is the perfect age to be disgraced but excellent investigative journalist Mikael Blomkvist; and Christopher Plummer is expansively patriarchal as Henrik Vanger, the wealthy industrialist who inadvertently brings the two together to solve a forty-year-old crime: the loss of his beloved niece. It’s not all Agatha Christie innocence, however: you will be disturbed, by the outcome and also by many scenes disturbing in both sexual and non-sexual gore (Lisbeth’s relationship with her new guardian Bjurman—Yorick van Wageningen—is especially something you’ll want to cover your eyes for.) The growing friendship between youthful Salander and craggy Blomkvist is convincing and enjoyable to witness; the peripheral characters are portrayed just about as you’d imagine them. On a visual level, Fincher perhaps overtakes Oplev purely because where Oplev sees the place he lives and conveys it in a natural way, Fincher sees it from our non-Swedish perspective, revealing the white, icy beauty and Ikea-white angles of homes and buildings. His intro, also, is quite mind-blowing, as a soft, tender tinkly piano barrels into a tar and sweat-soaked Karen O intro as Mara and Craig sex things up in an edgy, oiled-up way along with an eagle, a snake, and some raunchy flowers. Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor score the whole flick with requisite rage and gentleness.

Lisbeth’s use of Google and Wikipedia to track someone down seems to undermine her enormous talent in the hacking field; the Swedish accents sometimes slip; I felt that despite the epic running time—nearly three hours—Lisbeth’s storyline was not given enough time; during a Eureka moment for Blomkvist he makes such a ridiculous show of taking off his glasses in mute shock it seemed like a cliché in what is otherwise a very cliché-free movie; and in frustratingly Hollywood way of thinking, female Rooney is given countless crotch shots and appears fully naked frequently while male Blomkvist (who is polyamorous and hardly a prude) reveals his chest and the barest hint of butt-crack.

Still, these facts don’t at all ruin the film. Fincher’s use of actors in their natural, often makeup-free state is commendable (and something I enjoyed about the first movie trilogy); the long running time doesn’t mean the movie drags—it’s enthralling from start to finish; Mara’s Salander, like Noomi Rapace in the Swedish version, is an absolute treat of a character, scarred from a lifetime of people screwing her over but with a raspy charm all her own: wearing a t-shirt saying “Fuck you you fucking fuck”, explaining Blomkvist’s background to the man who has hired her: “Sometimes he performs cunnilingus. Not often enough in my opinion”—she really is amazing and is the new style of heroine everyone says she is. It passes the Bechdel Test (barely) and, in Sweden, is called Men who Hate Women, so the women are smart and not underwritten.

By all means, go see it if you’re unable to see the Swedish version—it’s a well-crafted film telling a wholly interesting and grotesque family crime story. But without it showing me anything new about the story (which admittedly, I have possibly overdosed on), it is still a vaguely pointless exercise. Because of this, and my clear ragey bias about it, I’m not going to give this movie a rating. See it for yourselves and let me know what you think.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is out January 12.

Attack the Block begins with a bunch of teenage miscreants mugging a young woman named Sam (Jodie Whittaker) at knifepoint in the a London street. During the altercations, an alien shoots from the sky, whereupon the kids beat the thing to death then parade it around on a stick. At this point, you’re pretty much thinking, great, I hope this alien’s friends fly down and kick the shit out of all these kids and claim the tall flats they live in as their base. I, for one, welcomed our new alien overlords.

Attack the Block begins with a bunch of teenage miscreants mugging a young woman named Sam (Jodie Whittaker) at knifepoint in the a London street. During the altercations, an alien shoots from the sky, whereupon the kids beat the thing to death then parade it around on a stick. At this point, you’re pretty much thinking, great, I hope this alien’s friends fly down and kick the shit out of all these kids and claim the tall flats they live in as their base. I, for one, welcomed our new alien overlords.

But then you end up following these kids through their incompetent attempts to defeat the sudden influx of aliens and, dammit, after a while you don’t want them to die after all. Led by moodily attractive teenager Moses (John Boyega), the gang come across as quite threatening to begin with until you realise that actually they are all pretty incompetent because they are, well, yoof. It’s Guy Fawkes Night, and they were out to create havoc and striving to be part of the gang led by the block’s main criminal mastermind, Hi-Hatz (Jumayn Hunter). Just as they finally strike it lucky enough to actually be on their path to, well, jail, more aliens rain down on them and everything changes, seeing the gang on the wrong side of everyone, from the police to Hi-Hatz to an irate Sam.

Having kids be the protagonists for a horror/sci-fi movie is pretty interesting, especially when director Joe Cornish chooses to be open about the facts that not all accidental alien-hunters are going to be as skilled as the team from Predators. These are kids who don’t have guns or fighting skills, but instead heed the call to arms with baseball bats, firecrackers, kitchen knives and false bravado. When shit gets real and they finally twig that they’re out of their depth, they can’t call for help because they’ve all run out of mobile phone credit; when they speed down staircases on their pushbikes they inevitably crash into the ground because they are not bicycle parkour enthusiasts. Despite the fact that the majority live quite standard home lives, getting told off by their mothers or told to keep out of trouble by their nannas, they’re all too desperately rough to turn to the grown-ups when being chased by deadly critters. And that’s the other thing, with them being kids: even though the movie is kind of funny, it’s not a balls-out comedy which makes it all the more surprising when you realise that not all of the teenagers are going to live out the film.

The film briefly touches on the state of British youth, when Moses speculates that the aliens have been sent by the Feds to kill the African-British because “we’re not killing each other fast enough”. It’s a nice try, but the fact that the kids, apart from Moses himself, seem to have fairly happy upbringings and some kind of self-awareness of what they’re getting into, means the movie doesn’t go far enough down that path, and you’re not even sure if any of the gang have learned a lesson by the end of it.

Nice touches are the aliens themselves: neon-fanged black holes of colour with no depth, like an orang-utan shagged a yeti in a dark cupboard using a glow-in-the-dark condom with a hole in it. The idea that colour shading would be different on a different hadn’t occurred to me and I thought it was really interesting, to be honest; it makes them shadowy and creepy even when they’re in a brightly-lit flat. It isn’t laugh-a-minute funny (which, as it’s from the writer of Hot Fuzz and stars Nick Frost, I was expecting), but it’s pretty amusing and the dialogue between the kids (who are also great actors) can be pretty hilarious at times. The two nine-year-old boys looking up to the gang are probably the comedy relief, flinging around tough phrases in high-pitched voices. It passes the Bechdel Test and the women in it—Sam, an elderly neighbour, and the girls the gang are all interested in—are pretty kick-ass, either physically or verbally.

Nick Frost’s high billing probably has to do with his star power more than his subdued role as a stoner in the only “safe house” in the building, though he and befringed try-hard Brewis (Luke Treadaway) smoke their way through some fairly funny moments. It was a fun movie that somehow missed a vital point with me, though I can’t think exactly what; I’d recommend it happily, even though it wasn’t quite cranked up all the way on either the funny, poignant, sci-fi or horror dials.

I give Attack the Block seven out of ten rows of glowing teeth. Because rows of teeth are SCARY.

Despite my general lack of knowledge about the intricacies of politics, I don’t mind watching movies with a political bent. After I wrote that sentence, I had a think about political movies and realised that they’re mostly satires (and I do love a good opportunity to say “Oooohhh, sick presidential burn”) or thrillers (“No, Mr President! There’s a bomb on Air Force One!”) and political dramas are not that common. Perhaps it’s because it’s a very limited point of view—to discuss politics in depth you often have to know how one particular country’s system works—or maybe because it gets played out on the news every damn day and you need something much more interesting to make people want to pay to see those in power tell lies and wear power suits. The Ides of March succeeded, I’ll hazard a guess, by populating the movie with actors that everyone admires: George Clooney, Ryan Gosling, Paul Giamatti, Philip Seymour Hoffman. These are people who attach their names to things that are generally great, so even if the dramatic ad campaign for The Ides of March didn’t give much away—treachery! shouting! manipulation!—we all knew it would be worthwhile.

Despite my general lack of knowledge about the intricacies of politics, I don’t mind watching movies with a political bent. After I wrote that sentence, I had a think about political movies and realised that they’re mostly satires (and I do love a good opportunity to say “Oooohhh, sick presidential burn”) or thrillers (“No, Mr President! There’s a bomb on Air Force One!”) and political dramas are not that common. Perhaps it’s because it’s a very limited point of view—to discuss politics in depth you often have to know how one particular country’s system works—or maybe because it gets played out on the news every damn day and you need something much more interesting to make people want to pay to see those in power tell lies and wear power suits. The Ides of March succeeded, I’ll hazard a guess, by populating the movie with actors that everyone admires: George Clooney, Ryan Gosling, Paul Giamatti, Philip Seymour Hoffman. These are people who attach their names to things that are generally great, so even if the dramatic ad campaign for The Ides of March didn’t give much away—treachery! shouting! manipulation!—we all knew it would be worthwhile.

And that it is. Sometimes I feel with movies that are a bit out of my reach of knowledge that I will say they’re good just so I don’t appear to have missed the point (not in reviews, dear readers, you know I don’t lie to you—but in conversation); American politics are not my forte, but even so, I felt I had enough of a grasp of what was happening to follow it. And that it a very good thing indeed. George Clooney (who also directed) plays Governor Mike Morris, a Democrat who is not only handsome and charismatic but would clearly never be elected to any kind of office because he holds dear all those things that politicians should—tax the rich, be pro-choice—but never do because they would lose all funding and the conservative vote. It all adds up to someone it’s easy to get behind for the sake of the movie, anyway. It’s the primaries—which means his current battle is against another Democrat, Senator Pullman (Michael Mantell) to see who will win the right to go for the position of president. This whole enemy-within-your-own-party thing is a little strange and something not all countries do, but hey, for the purposes of the movie all you need to know is that Clooney wants to beat that other guy and rule the world, so even if you don’t know what primaries are, it doesn’t really matter. Assisting our beloved George on his campaign trail are his team of media-savvy folk, headed by Paul Zara (Hoffman) and Paul’s 2IC, the boy wonder Stephen Meyers (Oh-My-Gosling.) They do their best to get Morris saying the right things to the right people and round up the team of interns (including the lovely Molly Stearns, played by a very pale Evan Rachel Wood) to lead the way. Elsewhere, journalist Ida (Marisa Tomei, playing a normal person for once) is out for a scoop; Senator Pullman’s own campaign manager, Tom Duffy (Giamatti), has his eye on Steve; and Senator Thompson (Jeffrey Wright) holds all the cards for those who will pay. It all builds up to what seems like it will be a more overarching political drama until a particular scandal comes to light and changes everything, for everyone, for better or for worse.

The acting is unsurprisingly excellent, though Gosling (who is my favourite actor of the moment) can lapse into a pretty vacant stare sometimes which I find unnerving. The cinematography and Alexandre Desplat’s soundtrack make for very intimate drama—you feel unexpectedly involved in Steve’s life, despite knowing nothing about what he does outside of politics (probably nothing) or anything about his past (apart from that he’s possibly mad at his dad). The moment it is in danger of becoming, well, not slow but possibly mired in political heaviness, the tight script then takes the movie down a different path and reinvigorates everything. Sometimes you feel almost emotionally blank towards particular events, and then one seemingly throwaway comment will bring everything back to being quite personal and real. It really is an amazingly well-crafted movie, much like Clooney’s previous directorial effort Good Night and Good Luck.

Alas, it fails the Bechdel Test pretty solidly; there are women in it—Molly, Ida, Governor Morris’s wife Cindy (Jennifer Ehle)—but they are too busy being vampy, traitorous or motherly to have any time to talk to each other. After a quick check of the Bechdel Test website, someone even points out that there is a moment when Molly talks to a female doctor or nurse, but the scene is completely without sound. It seemed poignant at the time, but upon reflection, well, no. Women are not given enough to do in this movie, and it’s disappointing, to be honest.

I give it seven and a staircase out of ten levels of the top levels of the United Nations (and that, my friends, is a reference in the film that I did not understand at all.)

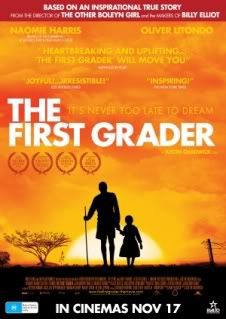

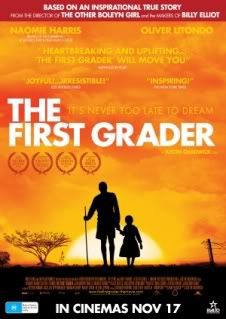

Kenya, 2004: the government has just announced that school is now free for everyone, and kids everywhere launch themselves at high speed—I’m not even joking—at the nearest classroom. Woefully undersupplied and with only 50 desks for the 200 kids there, one particular school is doing it tough. And one more student is determined to attend: 84-year-old Kimani N’gan’ga Maruge (Oliver Litondo), survivor of a brutal uprising fifty years earlier, desperate to get the education he never did, and learn to read so he can understand an important letter he has received in the mail.

Kenya, 2004: the government has just announced that school is now free for everyone, and kids everywhere launch themselves at high speed—I’m not even joking—at the nearest classroom. Woefully undersupplied and with only 50 desks for the 200 kids there, one particular school is doing it tough. And one more student is determined to attend: 84-year-old Kimani N’gan’ga Maruge (Oliver Litondo), survivor of a brutal uprising fifty years earlier, desperate to get the education he never did, and learn to read so he can understand an important letter he has received in the mail.

The story of Maruge’s taken-from-real-life trials, from the past to the film’s present, are in turns uplifting and devastating, the whole film perfectly pitched for the M rating it has in Australia but far too heartbreaking and reality-based for me to really try and be funny about. The children, singing, getting up to shenanigans and being generally adorable, lighten the tone, as does Maruge himself, who is clearly a man of hope. This is further strengthened when the viewer is pulled into his past, an unfathomable place of violence and horror where your toes and your children will be taken without a thought. Witnessing these scenes is nothing short of horrible and I was openly weeping in the theatre during them. You probably will too, and you’ll know what I’m talking about when it happens. The movie tugs at heartstrings in small ways and large, from moments as dramatic as the spilling of blood or as poignant as watching Maruge’s desperate plight to get into the school in the first place—told he can’t be there without the proper uniform, he uses part of his meagre savings to buy pants and turns them into shorts himself, then turns up in black shoes, long striped socks, shorts, a shirt and a blue jumper. His spirit is what buoys the film; his, and his teacher’s. Jane Obinchu (Naomie Harris) is determined to see him get taught despite the risks both professional and physical she brings upon herself by doing so.

There are moments of obvious exposition at the start, with Maruge remembering his wife and children as he moves about his home, and Jane on the porch with her husband as he tries to convince her to live in Nairobi with him and make babies while she tells him clearly that she wants to help the school. Despite radio announcements about Maruge’s schooling and journalists from the likes of the BBC shoving microphones in his face, you never really get a feel for the scope of Maruge’s influence locally or worldwide on a personal level. Rumours start about people being angry but it’s unconvincing; none of the parents ever come up to the school and give any valid reason why, and one permanently sour-looking father does a lot of glaring and is dangerously proactive about it, then fades into the background instantly afterwards. These aren’t huge gripes, however; you know me, I can’t like anything without pointing at some things and barking, “But if I was director, that would be different! Also there would be smell-o-vision and more Danny Trejo.”

Something as moving and hopeful as The First Grader needs to be seen to be believed, and you should see it. There are virtually no white people, and, thank the movie gods, none who come to save the day; it passes the Bechdel Test; Litondo’s acting is so expressive that he can make you want to cry just by staring into the distance; the enthusiasm of the kids for learning is infectious; the history lesson unforgettable; the message one we can all stand by: Learn. And don’t be an asshole. (I’m paraphrasing.)

I give it seven out of the ten tissues you’ll have to take with you.

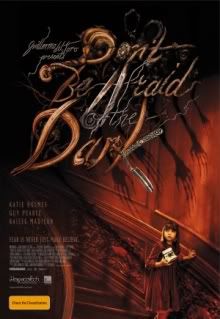

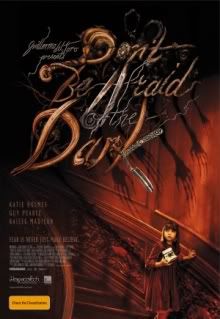

It may be a remake of a 1973 film, but it’s a good title, isn’t it? Of course we’re afraid of the dark; most scary movies would be nothing without shadows for bad guys to jump out of. And these bad guys are smaller than the ones you’re probably used to being scared of: tiny, withered monsters, freed from the grate of a basement. (These movies always make me glad that I’ve never been in a house with a basement, surely why Australia constantly tops “Liveable Country” Lists.) To be honest, this is pitched more at a younger market so most adults won’t be scared to go to the car in the dark after seeing the movie, but there’s a few scenes of genuine terror that might scare your kidlet out of losing the nightlight for, oh, fifteen years or so.

It may be a remake of a 1973 film, but it’s a good title, isn’t it? Of course we’re afraid of the dark; most scary movies would be nothing without shadows for bad guys to jump out of. And these bad guys are smaller than the ones you’re probably used to being scared of: tiny, withered monsters, freed from the grate of a basement. (These movies always make me glad that I’ve never been in a house with a basement, surely why Australia constantly tops “Liveable Country” Lists.) To be honest, this is pitched more at a younger market so most adults won’t be scared to go to the car in the dark after seeing the movie, but there’s a few scenes of genuine terror that might scare your kidlet out of losing the nightlight for, oh, fifteen years or so.

The central character of Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark’s all-round excellent cast is headed up by Bailee Madison as Sally, a young girl shipped from her mother’s possibly-over-medicating arms to her architect father Alex (Guy Pearce, not quirky for once), who is working on restoring an enormous mansion in Rhode Island. She’s instantly miserable, especially when she realises that her mother got rid of her indefinitely rather than briefly and that Alex’s girlfriend Kim (Katie Holmes, mostly dressed in sacks) is going to be sticking around. Just when living in a gigantic, beautiful mansion with two people who love you and a maid who makes apple pie seems like it couldn’t get any worse, the family uncover a basement hidden under the house, and unleash a tribe of stabby little gremlin-type monsters who love to feast on people. Well, specifically, people-bones. But will anyone believe a kid with a history of hardcore sulking? I mean, what would you believe if your clothes were found cut up: that it was your angry stepdaughter, or monsters that eat teeth?

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is getting some pretty bad press but it’s not really a terrible movie. Like virtually all recent horror flicks, it has a lot of flaws, but you could do worse than seeing this at the movies one night when you’re bored. The set design is amazing, the house’s landscape beautiful (with touches of Pan’s Labyrinth, thanks to the obvious touches from producer Guillermo del Toro) but unfortunately under-utilised. The actors, mostly Australian, are top-notch (and include, peripherally, Garry McDonald, apparently finally broken by his Mother & Son matriarch; Nicholas Bell as a greying therapist; Jack Thompson as the cranky but wise gardener), including Madison, who is an absolute treasure, delivering glares like a seasoned child-of-a-divorce but who ultimately just wants to be loved. (Aw.) A grotesque opening prologue delivers some serious cover-your-eyes squick straight away, and, as with all these types of films, it is endlessly frustrating yet understandable when people—especially adults—won’t believe you when you tell them there’s monsters out to get you. And these monsters are pretty damn icky, perfectly rendered special effects-wise with not a moment when they don’t seem physically there. They are revealed early and come out in dim enough light to be seen pretty clearly; they hold up in the light but as with many monster-flicks lose something in the reveal. The ending, as well, is a shock when you are hoping for the happy-la-la ending of many teen-aimed horror films. One thing absolutely worth mentioning is that it passes the Bechdel Test repeatedly, with women talking a lot about a variety of things, and that I was unexpectedly thrilled to see that when the family got around in a car, Kim did all the driving and Alex sat in the passenger seat.

On the downside, the tension isn’t directed all that well; you’ll be nervous, but not scared. The creatures can take on a grown, ragey man but when confronted with a sobbing nine-year-old swipe at her without making contact just long enough for her to be saved. When people fall, it’s always right on their head so they get knocked out. (Why is this? Do they not know that if they stay unconscious more than a few seconds it usually means some serious brain damage? Pretty much everyone gets tripped/falls and bonks their head instead of breaking their outstretched arm like a normal person.) Not enough is made of Sally’s mental state; she turns up to the house on Adderall and a comment is made on her past, but instead of making this an interesting discussion about child mental illness they brush it away, assume the medication isn’t necessary and even after a violent incident, suspicion doesn’t fall on her (or anyone, even when the particular incident is clearly not self-inflicted. It’s actually really frustrating.) Kim comes across as pretty selfish at the start, which makes her hard to relate to; also, she and Alex have inappropriate conversations that Sally overhears at more than one different moment, the repetition of which which cheapens Sally’s initial hurt through the amazing power of cliché. Important moments become plot holes—why does Sally not point out the twitching critter arm to a crowd after she victoriously squashes one? Why do critters that like to eat children’s teeth NOT ONCE get referred to as Tooth Fairies? And to top it off, the survivors’ underwhelming reaction to the horrific ending left me full of a rage I dare not elaborate upon, because, well, spoilers.

It’s not excellent but not appalling, well produced and quite a pretty film. I wouldn’t take anyone younger than, say, twelve to see it, but it might really hit the mark for a youthful audience. Don’t avoid it, and don’t be afraid of it. I give it eleven out of twenty baby teeth.

Like the birthday kid at a swimming party, you’re thrown in in the deep end of this head-scratching psychological thriller and left to flail about helplessly for about the first half hour before someone throws you a flotation device, but even then, it’s maybe the equivalent of three ping-pong balls rather than a lifejacket. What this does have at the start is a brylcreemed Robert Ledgard (Antionio Banderas), craniofacial plastic surgeon extraordinaire who lives in a sprawling Spanish estate; Vera Cruz (Elena Anaya), a beautiful woman who wanders around a sparsely furnished room wearing nothing but a body stocking; and a house full of servants who seem totally at ease with the fact that Robert has a woman locked in a room in his house. Why she is there, why Robert has video cameras in her room that feed into his wall-sized television and why Marilia (Marisa Paredes)—his longtime housekeeper—is so complicit in the captivity so badly is the soul of the story, told back and forth in time from the death of Robert’s wife up to the present (actually the future, as it’s set in February 2012.)

Like the birthday kid at a swimming party, you’re thrown in in the deep end of this head-scratching psychological thriller and left to flail about helplessly for about the first half hour before someone throws you a flotation device, but even then, it’s maybe the equivalent of three ping-pong balls rather than a lifejacket. What this does have at the start is a brylcreemed Robert Ledgard (Antionio Banderas), craniofacial plastic surgeon extraordinaire who lives in a sprawling Spanish estate; Vera Cruz (Elena Anaya), a beautiful woman who wanders around a sparsely furnished room wearing nothing but a body stocking; and a house full of servants who seem totally at ease with the fact that Robert has a woman locked in a room in his house. Why she is there, why Robert has video cameras in her room that feed into his wall-sized television and why Marilia (Marisa Paredes)—his longtime housekeeper—is so complicit in the captivity so badly is the soul of the story, told back and forth in time from the death of Robert’s wife up to the present (actually the future, as it’s set in February 2012.)