Confronted with the looming reality of his death, George Washington Crosby lies in the middle of his living room, on a rented hospital bed, surrounded by his family. With the medication taking hold and his body failing him, time becomes a loose construct and the life he has lived—as well as the life of his father before him—become as immediate as reality.

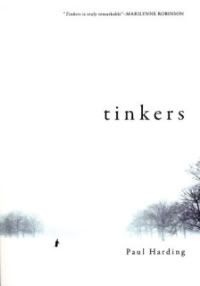

Confronted with the looming reality of his death, George Washington Crosby lies in the middle of his living room, on a rented hospital bed, surrounded by his family. With the medication taking hold and his body failing him, time becomes a loose construct and the life he has lived—as well as the life of his father before him—become as immediate as reality.In the unforgiving landscape of rural late-eighteenth to early-nineteenth-century Northern America, Howard Crosby sells goods, his mule pulling a cart full of life’s necessities; pins, coffee, tobacco. In a place where winter brings no income because his neighbours become reclusive and hunker down for it, it is a difficult living, his own violent epileptic seizures sometimes hindering his route. Howard’s observations of the landscape around him make for incredible reading; eloquent and as convincing as if Paul Harding was there seeing it for himself, and looking remarkably young now for someone pushing a hundred and fifty. Later, Howard’s son George will tinker with clocks, his relationship with his father and time always close at hand. Interspersed with beautiful meditations on Latin phrases and notations on the workings and history of clocks, to whittle it down to a story of a man and his father is to miss the beauty of this novel, which is the writing itself. Harding’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel is an original, captivating book that deserves its accolades.

One of the most astounding aspects of this book was the relationships between fathers and sons, not only between George and Howard, but between Howard and his own mentally declining father. Generally, when you read books or see movies set in such a time and place, guidance usually involves a whupping, or a disowning, or getting killed with your daddy’s shotgun, or perhaps all three, as the mother stands by feeling sad but unable to convey her emotions because of the general fear surrounding The Patriarch. In this, the fathers suffered from illnesses, but were good men, kind to their families and only wanting the best for their children. Until this book (admittedly not a true story) I had assumed that Nice Dads only appeared when beating your children started to seem more like picking on those unable to fight back, which didn’t seem to happen until the late twentieth century (and still hasn’t seeped into everyday consciousness, alas.) Possibly a meditation on how only men considered weak were able to show their children tenderness and affection, it was truly touching.

I was originally going to say that the one flaw of the book was that it was so mired in Harding’s elaborate language that I sometimes got a little overwhelmed by what was possibly hallucination, possibly symbolism, likely both, and kind of skipped over it. I’m usually in a hurry to get to the end of the book, where they all live happily ever after or die in a big explosion or what have you, so I don’t give some writing the time it deserves. I feel that the best books are those that work on two levels: a good, entertaining read for those like me who find speed reading a competition with no other competitors, and something with depth and beard-stroking metaphors for those who enjoy a ponder, or for me to think about later. I thought it possibly failed on the first front, because the hallucinatory nature of the language meant I got impatient very quickly with what was happening. Having said that, without even trying I’ve written about what I interpreted it saying about fathers, and he might have meant nothing by it. But it got me thinking and pretending to be analytical, didn’t it? So instead I’ll say the flaw of this particular edition was that I found at least three typos. And now I’m off to do my duty and type up my letter explaining why that is enough to strip Harding of his Pulitzer and give it to Jeff Kinney for the newest Diary of a Wimpy Kid book.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Opinions, opinions! Come one, come all.