Despite my general lack of knowledge about the intricacies of politics, I don’t mind watching movies with a political bent. After I wrote that sentence, I had a think about political movies and realised that they’re mostly satires (and I do love a good opportunity to say “Oooohhh, sick presidential burn”) or thrillers (“No, Mr President! There’s a bomb on Air Force One!”) and political dramas are not that common. Perhaps it’s because it’s a very limited point of view—to discuss politics in depth you often have to know how one particular country’s system works—or maybe because it gets played out on the news every damn day and you need something much more interesting to make people want to pay to see those in power tell lies and wear power suits. The Ides of March succeeded, I’ll hazard a guess, by populating the movie with actors that everyone admires: George Clooney, Ryan Gosling, Paul Giamatti, Philip Seymour Hoffman. These are people who attach their names to things that are generally great, so even if the dramatic ad campaign for The Ides of March didn’t give much away—treachery! shouting! manipulation!—we all knew it would be worthwhile.

Despite my general lack of knowledge about the intricacies of politics, I don’t mind watching movies with a political bent. After I wrote that sentence, I had a think about political movies and realised that they’re mostly satires (and I do love a good opportunity to say “Oooohhh, sick presidential burn”) or thrillers (“No, Mr President! There’s a bomb on Air Force One!”) and political dramas are not that common. Perhaps it’s because it’s a very limited point of view—to discuss politics in depth you often have to know how one particular country’s system works—or maybe because it gets played out on the news every damn day and you need something much more interesting to make people want to pay to see those in power tell lies and wear power suits. The Ides of March succeeded, I’ll hazard a guess, by populating the movie with actors that everyone admires: George Clooney, Ryan Gosling, Paul Giamatti, Philip Seymour Hoffman. These are people who attach their names to things that are generally great, so even if the dramatic ad campaign for The Ides of March didn’t give much away—treachery! shouting! manipulation!—we all knew it would be worthwhile.

And that it is. Sometimes I feel with movies that are a bit out of my reach of knowledge that I will say they’re good just so I don’t appear to have missed the point (not in reviews, dear readers, you know I don’t lie to you—but in conversation); American politics are not my forte, but even so, I felt I had enough of a grasp of what was happening to follow it. And that it a very good thing indeed. George Clooney (who also directed) plays Governor Mike Morris, a Democrat who is not only handsome and charismatic but would clearly never be elected to any kind of office because he holds dear all those things that politicians should—tax the rich, be pro-choice—but never do because they would lose all funding and the conservative vote. It all adds up to someone it’s easy to get behind for the sake of the movie, anyway. It’s the primaries—which means his current battle is against another Democrat, Senator Pullman (Michael Mantell) to see who will win the right to go for the position of president. This whole enemy-within-your-own-party thing is a little strange and something not all countries do, but hey, for the purposes of the movie all you need to know is that Clooney wants to beat that other guy and rule the world, so even if you don’t know what primaries are, it doesn’t really matter. Assisting our beloved George on his campaign trail are his team of media-savvy folk, headed by Paul Zara (Hoffman) and Paul’s 2IC, the boy wonder Stephen Meyers (Oh-My-Gosling.) They do their best to get Morris saying the right things to the right people and round up the team of interns (including the lovely Molly Stearns, played by a very pale Evan Rachel Wood) to lead the way. Elsewhere, journalist Ida (Marisa Tomei, playing a normal person for once) is out for a scoop; Senator Pullman’s own campaign manager, Tom Duffy (Giamatti), has his eye on Steve; and Senator Thompson (Jeffrey Wright) holds all the cards for those who will pay. It all builds up to what seems like it will be a more overarching political drama until a particular scandal comes to light and changes everything, for everyone, for better or for worse.

The acting is unsurprisingly excellent, though Gosling (who is my favourite actor of the moment) can lapse into a pretty vacant stare sometimes which I find unnerving. The cinematography and Alexandre Desplat’s soundtrack make for very intimate drama—you feel unexpectedly involved in Steve’s life, despite knowing nothing about what he does outside of politics (probably nothing) or anything about his past (apart from that he’s possibly mad at his dad). The moment it is in danger of becoming, well, not slow but possibly mired in political heaviness, the tight script then takes the movie down a different path and reinvigorates everything. Sometimes you feel almost emotionally blank towards particular events, and then one seemingly throwaway comment will bring everything back to being quite personal and real. It really is an amazingly well-crafted movie, much like Clooney’s previous directorial effort Good Night and Good Luck.

Alas, it fails the Bechdel Test pretty solidly; there are women in it—Molly, Ida, Governor Morris’s wife Cindy (Jennifer Ehle)—but they are too busy being vampy, traitorous or motherly to have any time to talk to each other. After a quick check of the Bechdel Test website, someone even points out that there is a moment when Molly talks to a female doctor or nurse, but the scene is completely without sound. It seemed poignant at the time, but upon reflection, well, no. Women are not given enough to do in this movie, and it’s disappointing, to be honest.

I give it seven and a staircase out of ten levels of the top levels of the United Nations (and that, my friends, is a reference in the film that I did not understand at all.)

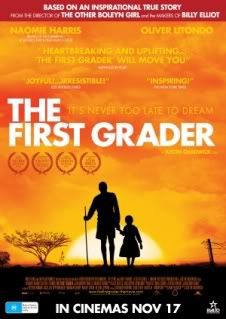

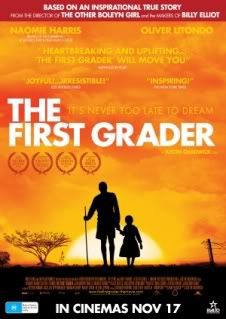

Kenya, 2004: the government has just announced that school is now free for everyone, and kids everywhere launch themselves at high speed—I’m not even joking—at the nearest classroom. Woefully undersupplied and with only 50 desks for the 200 kids there, one particular school is doing it tough. And one more student is determined to attend: 84-year-old Kimani N’gan’ga Maruge (Oliver Litondo), survivor of a brutal uprising fifty years earlier, desperate to get the education he never did, and learn to read so he can understand an important letter he has received in the mail.

Kenya, 2004: the government has just announced that school is now free for everyone, and kids everywhere launch themselves at high speed—I’m not even joking—at the nearest classroom. Woefully undersupplied and with only 50 desks for the 200 kids there, one particular school is doing it tough. And one more student is determined to attend: 84-year-old Kimani N’gan’ga Maruge (Oliver Litondo), survivor of a brutal uprising fifty years earlier, desperate to get the education he never did, and learn to read so he can understand an important letter he has received in the mail.

The story of Maruge’s taken-from-real-life trials, from the past to the film’s present, are in turns uplifting and devastating, the whole film perfectly pitched for the M rating it has in Australia but far too heartbreaking and reality-based for me to really try and be funny about. The children, singing, getting up to shenanigans and being generally adorable, lighten the tone, as does Maruge himself, who is clearly a man of hope. This is further strengthened when the viewer is pulled into his past, an unfathomable place of violence and horror where your toes and your children will be taken without a thought. Witnessing these scenes is nothing short of horrible and I was openly weeping in the theatre during them. You probably will too, and you’ll know what I’m talking about when it happens. The movie tugs at heartstrings in small ways and large, from moments as dramatic as the spilling of blood or as poignant as watching Maruge’s desperate plight to get into the school in the first place—told he can’t be there without the proper uniform, he uses part of his meagre savings to buy pants and turns them into shorts himself, then turns up in black shoes, long striped socks, shorts, a shirt and a blue jumper. His spirit is what buoys the film; his, and his teacher’s. Jane Obinchu (Naomie Harris) is determined to see him get taught despite the risks both professional and physical she brings upon herself by doing so.

There are moments of obvious exposition at the start, with Maruge remembering his wife and children as he moves about his home, and Jane on the porch with her husband as he tries to convince her to live in Nairobi with him and make babies while she tells him clearly that she wants to help the school. Despite radio announcements about Maruge’s schooling and journalists from the likes of the BBC shoving microphones in his face, you never really get a feel for the scope of Maruge’s influence locally or worldwide on a personal level. Rumours start about people being angry but it’s unconvincing; none of the parents ever come up to the school and give any valid reason why, and one permanently sour-looking father does a lot of glaring and is dangerously proactive about it, then fades into the background instantly afterwards. These aren’t huge gripes, however; you know me, I can’t like anything without pointing at some things and barking, “But if I was director, that would be different! Also there would be smell-o-vision and more Danny Trejo.”

Something as moving and hopeful as The First Grader needs to be seen to be believed, and you should see it. There are virtually no white people, and, thank the movie gods, none who come to save the day; it passes the Bechdel Test; Litondo’s acting is so expressive that he can make you want to cry just by staring into the distance; the enthusiasm of the kids for learning is infectious; the history lesson unforgettable; the message one we can all stand by: Learn. And don’t be an asshole. (I’m paraphrasing.)

I give it seven out of the ten tissues you’ll have to take with you.

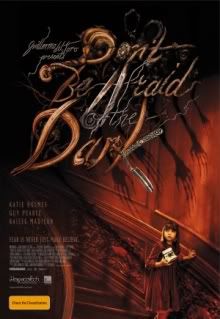

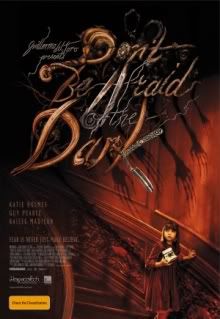

It may be a remake of a 1973 film, but it’s a good title, isn’t it? Of course we’re afraid of the dark; most scary movies would be nothing without shadows for bad guys to jump out of. And these bad guys are smaller than the ones you’re probably used to being scared of: tiny, withered monsters, freed from the grate of a basement. (These movies always make me glad that I’ve never been in a house with a basement, surely why Australia constantly tops “Liveable Country” Lists.) To be honest, this is pitched more at a younger market so most adults won’t be scared to go to the car in the dark after seeing the movie, but there’s a few scenes of genuine terror that might scare your kidlet out of losing the nightlight for, oh, fifteen years or so.

It may be a remake of a 1973 film, but it’s a good title, isn’t it? Of course we’re afraid of the dark; most scary movies would be nothing without shadows for bad guys to jump out of. And these bad guys are smaller than the ones you’re probably used to being scared of: tiny, withered monsters, freed from the grate of a basement. (These movies always make me glad that I’ve never been in a house with a basement, surely why Australia constantly tops “Liveable Country” Lists.) To be honest, this is pitched more at a younger market so most adults won’t be scared to go to the car in the dark after seeing the movie, but there’s a few scenes of genuine terror that might scare your kidlet out of losing the nightlight for, oh, fifteen years or so.

The central character of Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark’s all-round excellent cast is headed up by Bailee Madison as Sally, a young girl shipped from her mother’s possibly-over-medicating arms to her architect father Alex (Guy Pearce, not quirky for once), who is working on restoring an enormous mansion in Rhode Island. She’s instantly miserable, especially when she realises that her mother got rid of her indefinitely rather than briefly and that Alex’s girlfriend Kim (Katie Holmes, mostly dressed in sacks) is going to be sticking around. Just when living in a gigantic, beautiful mansion with two people who love you and a maid who makes apple pie seems like it couldn’t get any worse, the family uncover a basement hidden under the house, and unleash a tribe of stabby little gremlin-type monsters who love to feast on people. Well, specifically, people-bones. But will anyone believe a kid with a history of hardcore sulking? I mean, what would you believe if your clothes were found cut up: that it was your angry stepdaughter, or monsters that eat teeth?

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is getting some pretty bad press but it’s not really a terrible movie. Like virtually all recent horror flicks, it has a lot of flaws, but you could do worse than seeing this at the movies one night when you’re bored. The set design is amazing, the house’s landscape beautiful (with touches of Pan’s Labyrinth, thanks to the obvious touches from producer Guillermo del Toro) but unfortunately under-utilised. The actors, mostly Australian, are top-notch (and include, peripherally, Garry McDonald, apparently finally broken by his Mother & Son matriarch; Nicholas Bell as a greying therapist; Jack Thompson as the cranky but wise gardener), including Madison, who is an absolute treasure, delivering glares like a seasoned child-of-a-divorce but who ultimately just wants to be loved. (Aw.) A grotesque opening prologue delivers some serious cover-your-eyes squick straight away, and, as with all these types of films, it is endlessly frustrating yet understandable when people—especially adults—won’t believe you when you tell them there’s monsters out to get you. And these monsters are pretty damn icky, perfectly rendered special effects-wise with not a moment when they don’t seem physically there. They are revealed early and come out in dim enough light to be seen pretty clearly; they hold up in the light but as with many monster-flicks lose something in the reveal. The ending, as well, is a shock when you are hoping for the happy-la-la ending of many teen-aimed horror films. One thing absolutely worth mentioning is that it passes the Bechdel Test repeatedly, with women talking a lot about a variety of things, and that I was unexpectedly thrilled to see that when the family got around in a car, Kim did all the driving and Alex sat in the passenger seat.

On the downside, the tension isn’t directed all that well; you’ll be nervous, but not scared. The creatures can take on a grown, ragey man but when confronted with a sobbing nine-year-old swipe at her without making contact just long enough for her to be saved. When people fall, it’s always right on their head so they get knocked out. (Why is this? Do they not know that if they stay unconscious more than a few seconds it usually means some serious brain damage? Pretty much everyone gets tripped/falls and bonks their head instead of breaking their outstretched arm like a normal person.) Not enough is made of Sally’s mental state; she turns up to the house on Adderall and a comment is made on her past, but instead of making this an interesting discussion about child mental illness they brush it away, assume the medication isn’t necessary and even after a violent incident, suspicion doesn’t fall on her (or anyone, even when the particular incident is clearly not self-inflicted. It’s actually really frustrating.) Kim comes across as pretty selfish at the start, which makes her hard to relate to; also, she and Alex have inappropriate conversations that Sally overhears at more than one different moment, the repetition of which which cheapens Sally’s initial hurt through the amazing power of cliché. Important moments become plot holes—why does Sally not point out the twitching critter arm to a crowd after she victoriously squashes one? Why do critters that like to eat children’s teeth NOT ONCE get referred to as Tooth Fairies? And to top it off, the survivors’ underwhelming reaction to the horrific ending left me full of a rage I dare not elaborate upon, because, well, spoilers.

It’s not excellent but not appalling, well produced and quite a pretty film. I wouldn’t take anyone younger than, say, twelve to see it, but it might really hit the mark for a youthful audience. Don’t avoid it, and don’t be afraid of it. I give it eleven out of twenty baby teeth.

Despite my general lack of knowledge about the intricacies of politics, I don’t mind watching movies with a political bent. After I wrote that sentence, I had a think about political movies and realised that they’re mostly satires (and I do love a good opportunity to say “Oooohhh, sick presidential burn”) or thrillers (“No, Mr President! There’s a bomb on Air Force One!”) and political dramas are not that common. Perhaps it’s because it’s a very limited point of view—to discuss politics in depth you often have to know how one particular country’s system works—or maybe because it gets played out on the news every damn day and you need something much more interesting to make people want to pay to see those in power tell lies and wear power suits. The Ides of March succeeded, I’ll hazard a guess, by populating the movie with actors that everyone admires: George Clooney, Ryan Gosling, Paul Giamatti, Philip Seymour Hoffman. These are people who attach their names to things that are generally great, so even if the dramatic ad campaign for The Ides of March didn’t give much away—treachery! shouting! manipulation!—we all knew it would be worthwhile.

Despite my general lack of knowledge about the intricacies of politics, I don’t mind watching movies with a political bent. After I wrote that sentence, I had a think about political movies and realised that they’re mostly satires (and I do love a good opportunity to say “Oooohhh, sick presidential burn”) or thrillers (“No, Mr President! There’s a bomb on Air Force One!”) and political dramas are not that common. Perhaps it’s because it’s a very limited point of view—to discuss politics in depth you often have to know how one particular country’s system works—or maybe because it gets played out on the news every damn day and you need something much more interesting to make people want to pay to see those in power tell lies and wear power suits. The Ides of March succeeded, I’ll hazard a guess, by populating the movie with actors that everyone admires: George Clooney, Ryan Gosling, Paul Giamatti, Philip Seymour Hoffman. These are people who attach their names to things that are generally great, so even if the dramatic ad campaign for The Ides of March didn’t give much away—treachery! shouting! manipulation!—we all knew it would be worthwhile.